Hello and welcome to part three of my four-part Pride-month series: Speculative Fiction and (My) Pride! In part one, Imagining Diverse Futures, I introduced the world of Star Trek and the narrative spaces it created for diversity and inclusivity through conscious clothing design choices. In part two, Bodies and Souls, I expanded the conversation to examine the next generation (pun definitely intended) of Trek franchises, as I analyzed an episode from each The Next Generation and Deep Space Nine in terms of love and identity.

Today’s entry is titled “Discovering Selves, Discovering Family,” and will use Star Trek: Discovery (Disco) as a launching point to shift the speculative fiction (spec-fic) conversation from Star Trek’s vision of a positive future to author Becky Chambers and her incredibly well-developed worlds that, to me, resonate profoundly with Trek’s ideals.

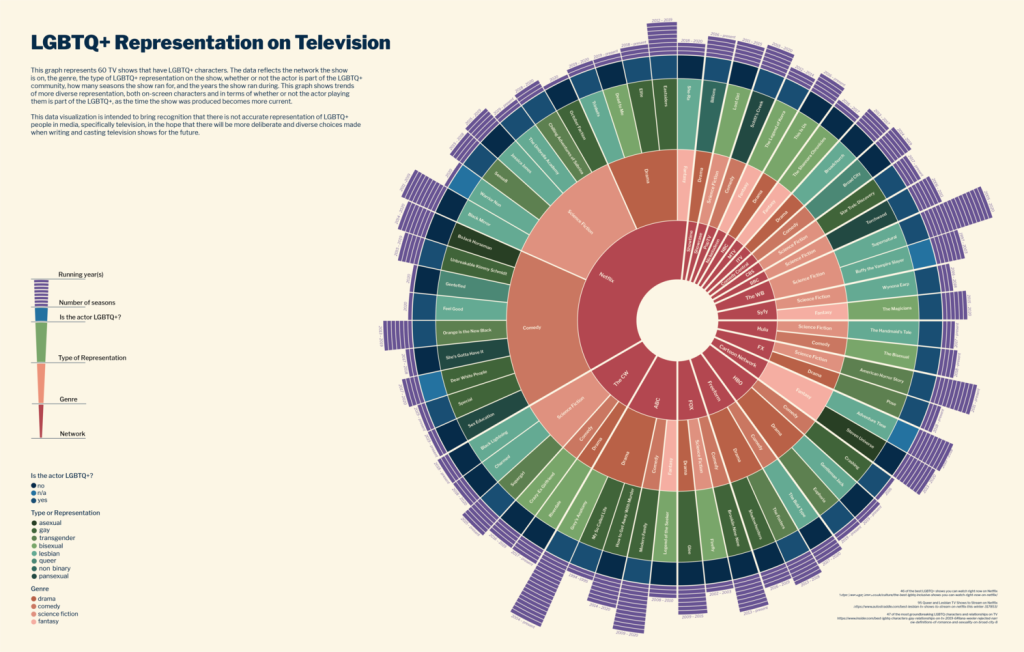

LGBTQ+ Representation on TV

Let’s start by examining this graph, a visual representation of 60 near-current shows with breakdowns of the representation types present on-screen (view the full-sized image):

Star Trek: Discovery appears on the top right quarter of the diagram, credited for including the character Paul Stamets, portrayed by openly-queer actor Anthony Rapp. Disco is a different kind of Star Trek, set approximately a decade before the events of The Original Series. The fifth and final season of Discovery is slated for later this year, but the first four seasons are a powerhouse of a show. I recommend it to anyone, especially if you’ve never watched any Star Trek before; no prior knowledge is necessary. Disco’s first claim to fame? The first canon (confirmed) queer couple: Mycelial engineer Paul Stamets and husband, Dr. Hugh Culber.

However, I think it’s a massive disservice to Disco, casually referred to as the “queerest Trek” by the cast, crew and fans alike, to base its LGBTQIA+ inclusivity solely on the Stamets and Culber relationship. The show does a mostly good job with their relationship: they kiss on screen, a first for Trek television for two men to smooch, brush teeth together, and express their deep love and devotion for each other verbally. This is the absolute bare minimum for Trek to offer LGBTQIA+ community members after 50+ years of diverse and inclusive narrative choices. While romance is never the central focus of Trek as a whole, romance narratives are present in every iteration and dominate the plots of episodes from every single season across the franchise. Disco’s first season may have been an attempt to bring queer people to an equitable place on screen, but the first season failed me in a few key ways, starting with the assumption that equity is a one-and-done mentality that doesn’t need to grow and adapt with the times.

The other unfortunate reality for queer characters is a trope named bury your gays. If you’re not familiar, a trope is a common or overused theme or device (think: enemies-to-lovers). When LGBTQIA+ characters are clearly defined and present but somehow killed or written off, they are shown to be more disposable than other characters. Often these deaths remove agency from the characters and make a spectacle of their decisions and even of their death. Hence the name, bury your gays. Sometimes writers will use the LGBTQIA+ character’s death as a means for a different character to undergo some type of trauma or development. The use of this trope for Culber was choppy and uncomfortable. While the writers did bring Culber back in season 2, there are an uncomfortable handful of episodes to get through.

Where the show succeeds, in my opinion, begins in the third season with the introduction of human teenager Adira.

Adira is the first known human to join with a symbiont and gets a really great self-discovery arc in that third season. Adira is an orphan, and while nearly an adult, they are still a teenager, and they begin to have a parent/child-esque relationship with Paul as he mentors them. They come out as nonbinary somewhere in there, telling Paul their pronouns are they/them. Paul smiles and says ok, and never mentions it again. It’s a great example of how to react to someone coming out to you, and I’ve included a video clip of the moment here:

What makes it better is later, when Paul is talking to his husband, Paul uses they/them to refer to Adira, and Hugh picks up on it immediately. There is never a scene where Adira has to explain to someone new, correct someone, or defend themselves. They are simply accepted as they are, and not just accepted, enthusiastically supported. Stamets has the best possible response to Adira in all regards, from being a safe person to come out to, to the way he models proper behavior with his husband.

The whole show is wonderful in this way, and while there are some aspects I wish they’d do differently, the overall impact is important. If one of the core tenets of Star Trek is and has always been “infinite diversity in infinite combinations,” then I think Discovery is doing a fantastic job bringing Trek more current with more LGBTQIA+ communities and starting to move beyond the narrative that LGBTQIA+ inclusivity=homosexual romance on screen. Adira’s late boyfriend, who returns to the show through some Trek science magic, is also transgender and played by the openly transmasculine actor Ian Alexander.

Ultimately, the Adira/Paul/Hugh dynamic forms a recognizable family unit, reinforcing a core tenet of Disco as a whole: the idea of found family. Season three culminates with an excellent speech from Commander Michael Burnham, played by the incredible Sonequa Martin-Green, before fading out to illuminate a Gene Roddenberry quote:

In a very real sense, we are all aliens on a strange planet. We spend most of our lives trying to reach out and communicate. If during our lifetime we could reach out and really communicate with just two people, we are indeed very fortunate.

-Gene Roddenberry

Disco consistently reinforces the idea of community and finding a space to belong. Flung out of time, the crew of the Discovery relies on each other, alone in the far future, to survive, adapt and grow. After 2 seasons of intense plot and world-building, they function as a team, as a family. Michael uses the word family often to speak with Starfleet Command in this future, referencing the cohesive manner in which her ship relies on each other and supports each other. It’s no stretch to see the creators of the show felt the same way. Season 3’s closing monologue from Michael is a reminder that at the core of each of us, we seek connectivity and companionship. We seek love.

Author Becky Chambers

It’s been far easier, in my experience, to find this kind of representation in the spec-fic of literature as compared to visual mediums. I can think of no better example which sticks to the same core values and tenets of Disco than the works of spec-fic author Becky Chambers.

Genres: Science-fiction; Speculative Fiction

First Publication: The Long Way to a Small, Angry Planet (2015)

Series: The Wayfarers; Monk & Robot

Call Number: SCI FI CHAMBERS

Eyan’s Rating: 5/5 overall

For Fans of: James S.A. Corey’s The Expanse series; If your favorite Star Trek series is Discovery.

About

Becky Chambers is a powerhouse in the speculative fiction world. Since her 2015 publication of The Long Way to a Small, Angry Planet, the first in her 4-book Wayfarers series, Chambers has continuously produced incredible works of speculative fiction with richly developed characters whose personal journeys reflect the nuance and variety of the human experience. The great thing about this particular series is you don’t necessarily need to read the books in order. While each subsequent book takes place chronologically after the preceding title, and some events have been predicated because of past plot points, each new book focuses on a new character or location, making it easier to move between titles.

The Wayfarers series is a world similar to, but different from, our own, with humans flung to the intergalactic realm and occupying a minority role on the galactic stage. My particular favorite book in the series is the second title, A Closed and Common Orbit, which follows Lovelace, the artificial intelligence from the first book, as she adjusts to a new form and a new life—with none of the memories of the life she had led before. It’s a story of love and identity; both because Lovey has to determine what it means to live in a humanoid body, determining questions of gender and language (even the choice of she/her is intentional) and because her relationships with the people around her represent all kinds of love, from familial to platonic and beyond. Lovey’s journey is deeply reflective of an adolescent coming-of-age narrative, and, for all her differences to the human experience, Chambers’ use of Lovey as the means by which she questions characteristics of gender identity is incredibly nuanced and provocative.

Because Lovey is a computer at her core (pun only mildly intended), her exploration of identity can be disconnected from our own while also raising the question of body and soul; if Lovey can move between ship and body, what is the relationship between body and soul? Is gender an inherent part of the soul’s experience? And how can we then relate Lovey’s journey to our own? Every book Chambers publishes has the same core theme: who are you at your heart, and how can we find belonging together? Chambers’s worlds are infinitely diverse, and any Trek fan will recognize her vision of a better future; the next generation of Roddenberry’s future.

Start reading the Wayfarers series

Becky Chambers’ books can be found on the 3rd floor under SCI FI CHAMBERS, and all of her titles are worth a read.