Hello and welcome to part two of my four-part Pride-month series: Speculative Fiction and (My) Pride! Last week I introduced the role of Star Trek as an influential piece of speculative fiction.

Today’s discussion, “Bodies and Souls,” will examine two very special episodes of Star Trek. These episodes are both very important to me. They both explore questions of love, relationships, identity and personhood, while probing the intersection of personal identity and romantic relationships. How much of yourself changes when you love someone?

Star Trek: The Next Generation season 5, episode 17, “The Outcast” (1992)

Star Trek: The Next Generation (TNG) follows a brand-new crew on the starship Enterprise. Aired from 1987 to 1994 over 7 seasons and 178 episodes, the cast of TNG is an entirely new generation of Starfleet officers, set in-universe about 95 years after TOS. TNG makes a number of changes to the world of Trek in no small part due to the 20-year gap between the creation of TOS and TNG. It is not always successful in navigating themes relevant to me as an LGBTQIA+ person, but the attempts are clearly there. One such episode is frequently discussed under these contexts, season 5, episode 17, titled, “The Outcast.”

The crew of the Enterprise is contacted for assistance by an alien race that has no gender, the J’naii. Commander William Riker, well known for his success in matters of love, falls in love with one of these aliens. The alien in question is named Soren, and while Soren comes from a species that has ‘moved beyond gender,’ Soren begins to assert a gendered identity and wants Riker to help.

Soren begins to express a feminine identity, expressing to Riker and other members of the Enterprise that she feels as though she is a woman, and wants to live as such. Additionally, she also understands her attraction to Riker as part of her womanhood—sexual desire for the opposite gender is not an experience her people go through, as there is only one “gender” for the J’naii. For his part, Riker is incredibly supportive of Soren, attempting to help her claim asylum with Starfleet so she doesn’t need to return to her people, where they intend to put her through a type of conversion therapy to “fix” her.

Conversion therapy of this sort is still legal in many states, and for an episode that aired in 1992, the conversation of gender, identity, and sexuality as separate pieces of personhood was very nuanced. I do have issues with this episode, of course, but taken in the context of the time, especially knowing that the original creator, Gene Roddenberry, was in favor of LGBTQIA+ inclusion on-screen, I think this type of episode was incredibly important. Further, Jonathan Frakes, the actor who portrays William Riker in all his on-screen appearances, has candidly spoken about this episode:

…And the character should have been cast as a man, I think… The network, or someone, didn’t have the guts to do that, so they cast an androgynous looking woman so Riker would not be perceived as gay, perhaps? I’m not quite sure what the thinking was. But it’s always seemed like a missed opportunity.

-Jonathan Frakes interview

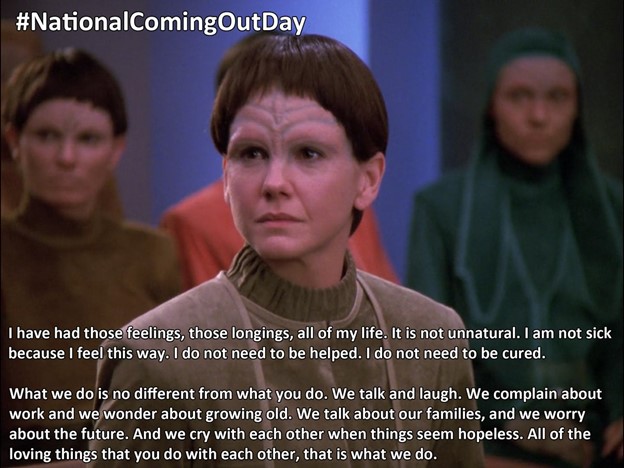

There isn’t a happy ending for Soren and Riker. Soren, despite her attempts at independence, is ultimately converted back to her planet’s version of the status quo, despite the intense association with the gender she expresses. In a profound moment of passion, she gives the following speech, which could come from any year between the episode’s original airing in 1992 and today, 21 years later, and I’d like Soren’s voice to be how we finish this episode’s discussion:

Star Trek: Deep Space Nine season 4, episode 6, “Rejoined” (1995)

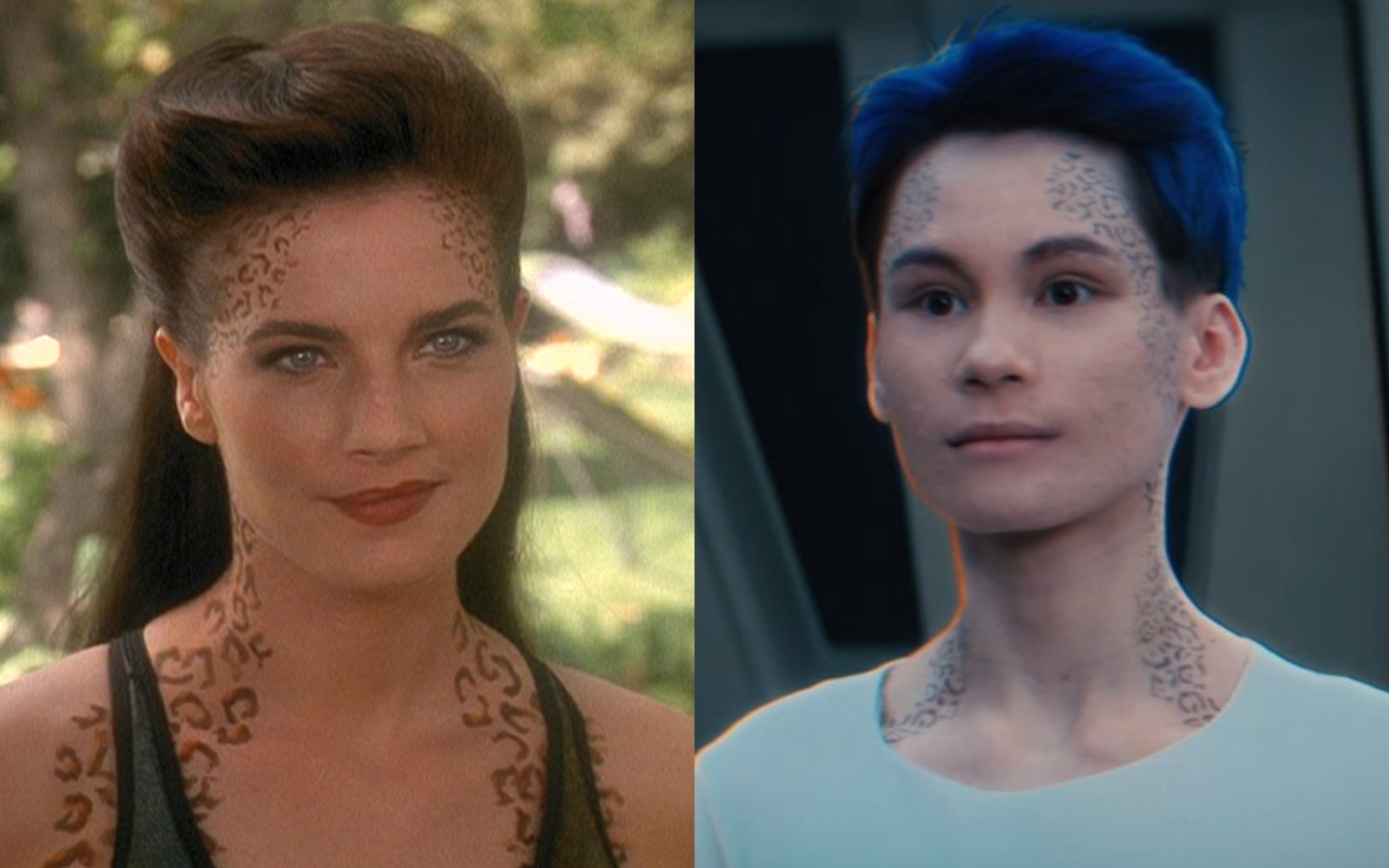

Three years later, Trek again pushed the boundaries of representation and diversity in the media with an episode in the fourth season of the franchise’s third series, Deep Space Nine. In this series, the alien race of the Trill is explored in more depth, as main cast member Jadzia Dax is a Trill Host. Trill are a humanoid species nearly indistinguishable from humans, besides the cute spots down their faces, arms and legs, but some of them can join with a sentient long-lived creature known as a symbiont, becoming a host, which is an amalgamation of the current body’s personality and all the memories, experiences and personalities of the symbiont’s previous hosts.

Jadzia is the Dax symbiont’s eighth host, and while she herself is a young 24-year-old woman, she has gained 7 lifetimes of experience when she joined the Dax symbiont a handful of years earlier. Her personality as Jadzia is well-developed and funny, but her role as a joined host also means aspects of other personalities are constantly present within her. She is also seen as a stand-in for the transgender, specifically transfeminine, experience, as her most recent previous host was a man named Curzon. However, Jadzia herself is also often read as a transgender woman, and the actress who plays her, Terry Ferrell, says that she played Jadzia to have a more complicated past regarding gender than might be otherwise assumed. Another fascinating aspect of Trill culture resides in the way other species respond to new hosts. While there is some confusion and discomfort in adjusting to a new host, the relationship Dax has with other characters, like Captain Sisko, adjusts to accommodate Jadzia as the person who best understands who and what Dax is. We get this amazing scene when an old Klingon friend of Curzon Dax meets Jadzia for the first time, and the moment has become a meme used for acceptance and love.

The one true taboo on Trill is against associating with past lives. Ostensibly this taboo is because the entire purpose of joining with a symbiont is so that the symbionts can learn something new and experience entirely new things, but occasionally this prohibition causes difficulties. In this episode, another Trill woman comes to the station, and we learn that the symbiont she hosts used to live in a different woman, one married to a previous male Dax host. However, because of the dual nature of joined Trill lives, both women remember the experience of loving each other and discuss continuing their relationship in these new lives. While the prescription against reaffiliation is ultimately too strong for the other woman, Jadzia has determined her feelings are profound enough to undergo exile from her home planet and species.

In both episodes here discussed, the question of love and sexuality is raised: if you love someone and their body changes, do you still love them? Is sex separate from love? I don’t think there are definitive answers in either show, but the questions themselves are important. So often, queer identities are overly sexualized; to show a lesbian kiss on screen was shocking, and this episode features the first. But the kiss, a closed-mouth, chaste kiss, is less graphic or long-lasting than most of the kisses depicted on screen in Trek by heterosexual characters.

Trek is no stranger to pushing< the envelope; the first televised interracial kiss happened in TOS’s third season episode “Plato’s Stepchildren,” and while that episode is problematic in many other ways, the usage of a televised kiss to make social commentary is nothing new for Trek. Where the series falls short, however, is in the specific open representation of queerness. I love that Jadzia had these deep emotions, and we shouldn’t need to question a person’s sexuality every time they fall in love with someone. However, especially in 1995, and even to this day, the lack of clear representation is still a major issue. The fact that Jadzia is never confirmed as queer/bi/pan/omni despite this female love interest and her future male husband is a major issue in representation, to me. There are likewise no confirmed queer characters in Trek from this point in 1995 to 2017, 22 years later, when Star Trek: Discovery launched.

Trek’s long history of queer coding, which often happens through clothing choices, as I touch on briefly in Part 1, gave narrative space to find queer identities during times when vocalizing those identities had very real repercussions. It has always been clear to me and many members of the LGBTQIA+ community that these spaces are spaces held for people like us to imagine ourselves in a Trek future. It is no longer enough, however, to silently open spaces wherein those outside the community can decide to exclude us. When subtext is the only space for queer identities, those identities become less visible, less acceptable and less diverse. We’ll talk about Disco’s attempts at explicit representation in my next installment. But if I can leave you with something to consider until then: when LGBTQIA+ represented is relegated to silent spaces and subtext, the nuanced reality of those identities becomes lost in the utilization of story tropes. Further, this reinforces a subconscious social ideal that pressures LGBTQIA+ identities to remain hidden and undiscussed, viewed as less important than or secondary to narratives that are viewed as “acceptably straight.”

The next time someone asks you why a character “needs” to be clearly defined as bisexual, transgender, asexual, demisexual, agender, two-spirit, intersex, or any of the myriad identities housed under the LGBTQIA+ umbrella, respond how I always do:

Why not?