ShortHaus Cinema is yet again featuring an artist-turned-director. Although we initially chose Ridley Scott for November because his new feature, Napoleon, will be coming out later in the month, he is also well-known for his artistic storyboards known as Ridleygrams. These storyboards are an integral part of his filmmaking process, without which his beautifully lit films could never be shot.

Ridley as Artist

Ridley Scott was born on November 30, 1937, in South Shields, County Durham, England, a working-class town. He had a stern mother and a military father, and growing up during WWII, his family was constantly moving. Scott always did quite poorly in school (he humorously framed a report card that ranked him 29th out of 29 students). But he thrived once he found his place in art school. He spent four years at West Hartlepool College of Art and another three at the Royal College of Art in London. And though he shifted to film in his final year, that early training in drawing and painting never left him.

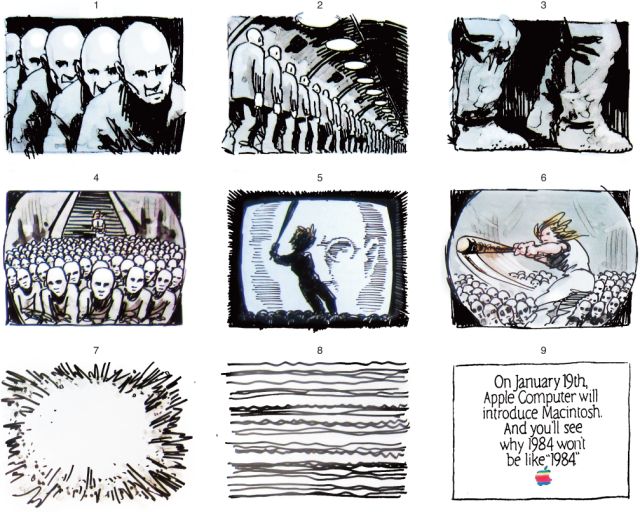

Scott spent the following decade making commercials, a medium whose brevity demands a strong visual design to communicate an idea quickly and clearly. In her 2017 book Off the Cliff: How the Making of Thelma & Louise Drove Hollywood to the Edge, Becky Aikman says this of his early career, “Each Ridley Scott commercial got the mini-masterpiece treatment, storyboarded, designed, lit with perfection and shot by Ridley himself.”

Ridleygrams for the famous 1984 Macintosh commercial

With the accelerated output in such a constrained medium, he was able to master his visual style. Now, for every film, the story is told before the cameras ever start rolling. As he reads the script, the scenes begin to play out in his mind. He’ll start small, drawing thumbnails to get the structure right, but often falls completely into them, adding finer details of shading and grime. He’ll work with his pre-production crew, revising and refining, until the film is plotted out scene by scene. By then, he says, “I’ve already filmed it on paper.”

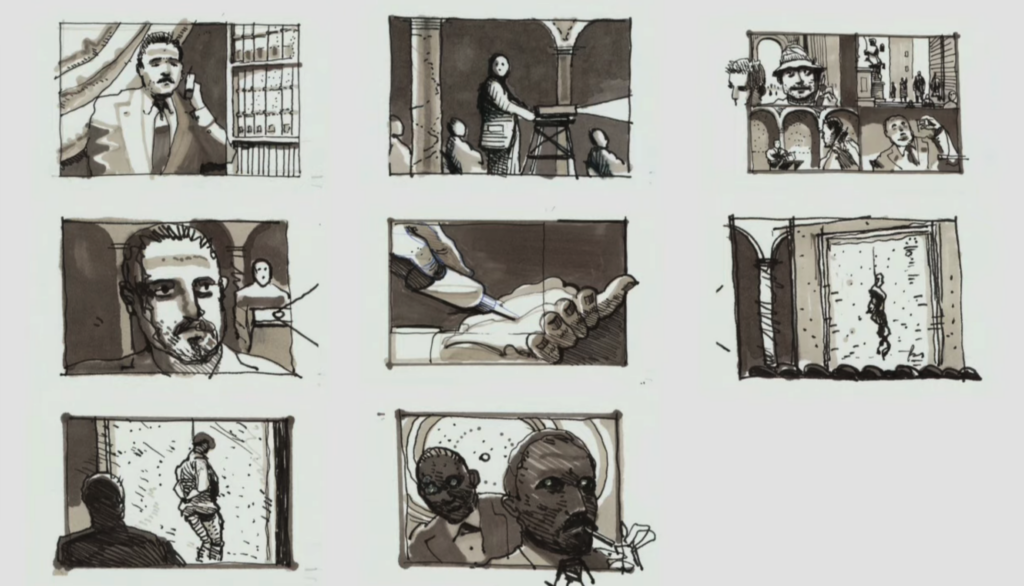

Ridleygrams for Hannibal (2001)

Drawing With Light

The art of drawing is literally the act of recording where light falls. Where the light is coming from, how strong it is and how close it is determines where each shadow lays. Light is what gives objects dimension and depth. The lighting team is then able to literally draw with light to make those initial storyboards come alive.

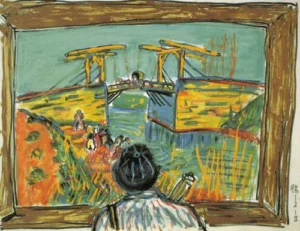

Kurosawa’s storyboard for “Crows,” from Dreams (1990), after van Gogh’s The Langlois Bridge at Arles (1888)

Akira Kurosawa (featured by ShortHaus back in August) is also a director well-known for his storyboards. He began his career as a painter, heavily influenced by Vincent van Gogh, before finding success in film. His storyboards are more expressive than Scott’s, focusing on dynamic movement and vibrant color, though there’s still a clarity that communicates what he needs from his crew.

Takeji Sano, a frequent collaborator with Kurosawa, and the lighting director on Kagemusha (1980) and Rhapsody in August (1991), describes the struggle they went through to get the perfect fishing lamps with specialty bulbs to submerge in a pool and achieve the perfect color for one key scene. A bit of a hassle, “but when you read the script and look at the storyboards, we couldn’t skimp on these lights.”

beautifully eerie, courtesy of fishing lamps

Kurosawa wasn’t always so focused on color. It took him several years after the standardization of color film techniques to move in that direction. He commented plainly, “Lighting is all wrong in current color movies.” The films were flat, lacking the delicious depth perfected in black-and-white films. When he finally did make the move to color, he had to be very particular about lighting. As described in the documentary A Message from Kurosawa: for Beautiful Movies, “The reflectors are colored to enhance the color he wants. Blue to enhance red, purple to enhance yellow, and so on. It’s as if he’s using techniques from an oil painting. That’s how colors in his film take on their depth”

on the set of Rhapsody in August, a crew paints blue lines onto metallic reflectors

vibrant reds, enhanced by those blue reflectors

Ridley Scott, on the other hand, detests using colored reflectors or gels for his lights. Instead, he favors moody backlight to give dimension to the characters and haze to create depth in every scene. Incense is constantly burning on his sets, and he passes out cigars to crew and off-camera actors so the smoke will drift into the scene. It’s not appreciated by everyone on set, but he relies on that dimensionality achieved only by light dancing around the fog.

Thelma and Louise, surrounded by haze, backlit by neon signs and reflective glassware

Thelma, beautifully backlit with multicolor haze, while Harlan stands in imposing shadow

With the storyboards on hand, Scott’s crew can get to work lighting each scene. Even the set dressers are tasked with getting the light right, incorporating reflective surfaces in every corner. For the bar scene in Thelma & Louise (1991), Becky Aikman reports that The Silver Bullet set “looked like a large, empty, beer-stained box before they got to work. They’d turned it into a Ridley Scott playground: crate loads full of clear glassware, neon beer signs on the walls, pool tables with blue billiard maps suspended overhead and a dance floor beckoning under red and blue lights that spun from the ceiling.” With all that dazzle and reflection, Thelma and Louise can shine, perfectly backlit in the color-shifting haze.

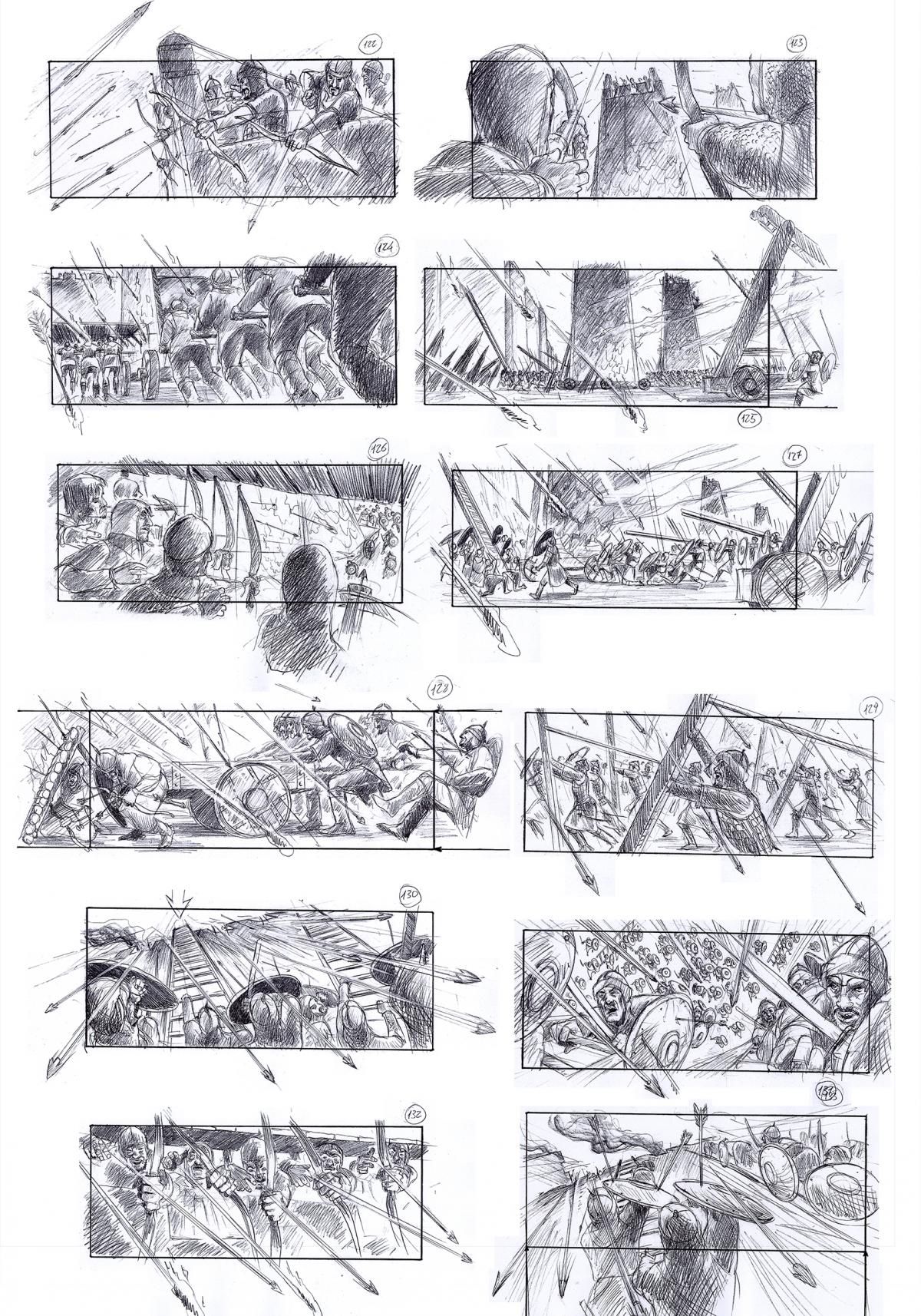

Ridleygrams for Kingdom of Heaven (2005), chaotic movement made clear

Kurosawa’s storyboards for Kagemusha

Discovery and Restraint

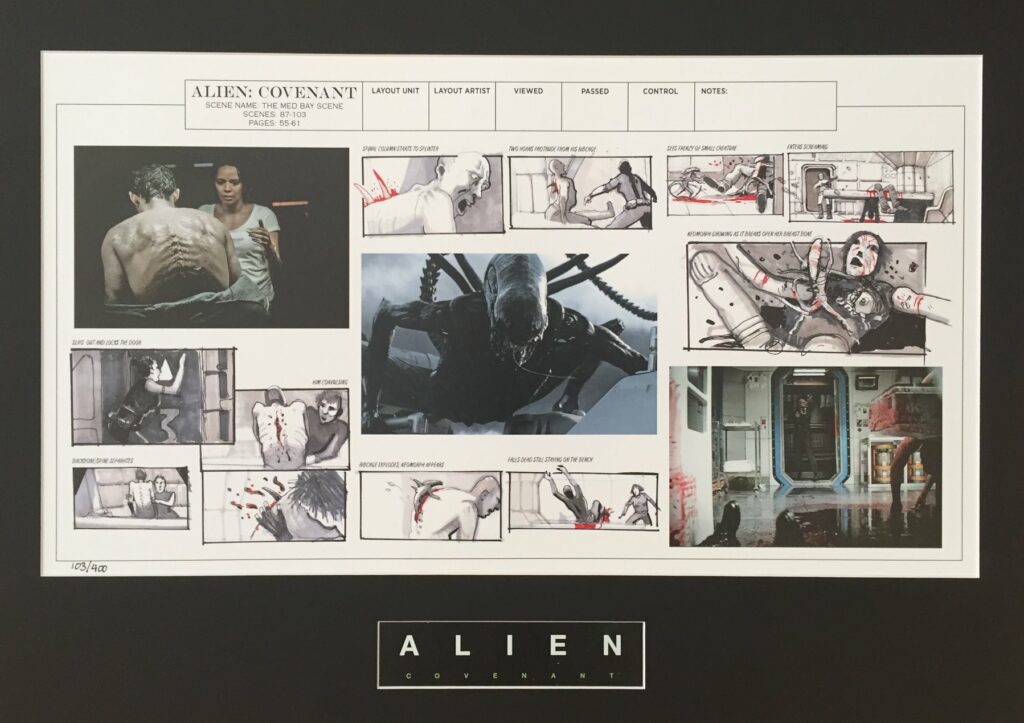

Through storyboarding, Ridley Scott is able to problem-solve. In his commentary for Alien: Covenant (2017), he says, “I know how to draw. Many years at art school, it was all hard work, but drawing now is very fast and easy for me, so I’ll turn up with, in sequences like this, actually boarded, shot-by-shot, wide, close, medium. So I’ll already get the tonality and the feeling for what it is and how savage it’s going to be.”

This is in response to the dastardly scene where his newest creation, the Neomorph, breaks out from its host mother. The brutality of the scene is carefully marked out, a slip in the blood here, a broken ankle there, and all telegraphed flawlessly to heighten the tension of an already terrifying scene.

Ridleygrams for Med Bay Scene in Alien: Covenant

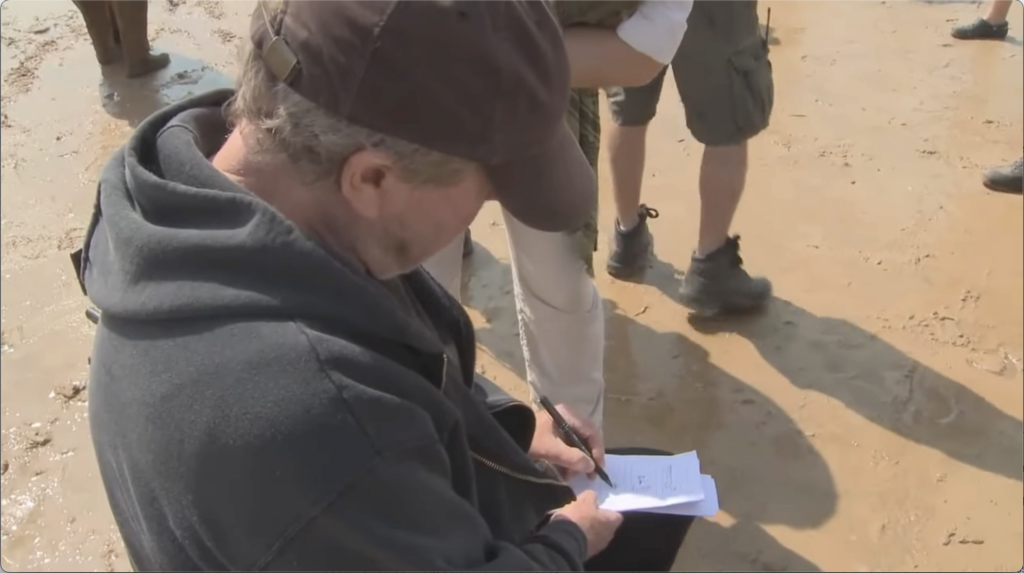

On set, too, Scott is still drawing. Always revising as he comes up with new ideas and births a revitalized scene. Kurosawa did this as well, communicating last-minute changes through quick drawings. In one example, Kurosawa saw one of his child actors stand on a railing and realized he needed to reframe the entire shot to incorporate this more playful blocking. So regardless of how carefully he planned, his film is always allowed to breathe and evolve. There’s creativity within constraints.

Ridley Scott drawing on set of Robin Hood (2010)

Akira Kurosawa drawing on set of Rhapsody in August

You May Not Be an Artist, But…

You need to storyboard. Storyboards are often undervalued in the art of filmmaking. When working on smaller projects, the process might be skipped with the thought of saving time. However, clear storyboards can save an exponential amount of time and money. Everything you figure out in pre-production reduces the hemming and hawing while actors and crew stand around and drain your budget, which is especially precious on indie projects.

Even if you’re working on a solo project, you can save so much time (and SD card space) just by planning your shots before hitting record. You don’t have to be an artist like Kurosawa or Scott. You can opt for simple figures, arrows for movement and a little bit of shading to see how the light falls. Now you know where the camera and lights need to go and what lens you need for each shot. Storyboarding and planning ahead are invaluable, and the more you incorporate them into your workflow, they will get easier and your projects will get better.

Now What?

If you’d like to learn more about lighting techniques, there are excellent tutorials available on LinkedIn Learning. And if you’d like to see more of Ridley Scott’s storyboards, The Making of Alien by J.W. Rinzler includes full-spread pages of his drawings for Alien (1979). If you’d like to see more of Akira Kurosawa’s storyboards, the Criterion edition of Kagemusha has them collected in the included booklet.

Sign up to get updates to see future posts and check out previous ShortHaus blogs.

ShortHaus Cinema is meeting to discuss Ridley Scott on Tuesday, November 7 at 7 p.m. in Meeting Room C. We’ll discuss his student film, Boy and Bicycle, available on Kanopy, and how to begin storyboarding your own projects. Join us, and together we will explore the art of storyboarding for film, following the impeccable example of Sir Ridley Scott!