ShortHaus’s next featured director is Jim Henson, a playfully prolific artist who modernized and revolutionized puppetry by adapting the centuries-old medium for television. (Fun fact: some scholars trace the origin of puppets to India 4000 years ago, where the main character in Sanskrit plays was known as Sutradhara, “the holder of strings.”)

Instead of performing his puppetry within the confines of a typical puppet theater (shown below), Henson pushed his Muppets right up to the camera and into our living rooms. This new perspective transformed television sets into the theater.

Abstracting the format also made his puppets more lifelike and expressive, just like cartoons that show a caricature of the real world through exaggerations. Henson’s style of puppetry allowed us to see an emotional truth beyond what could typically be expressed by the human face and body.

a traditional puppet theater

Sam and Friends was performed with sparse sets

Imperfections of CGI

Despite Henson’s refining of the craft, contemporary media has largely moved beyond puppets and practical effects and into the realm of the hyperreal. Computer-generated imagery (CGI) is a powerful tool capable of generating great vistas and impressive visual effects. An alien creature can look terrifyingly lifelike, covered in a sheen of slick textures, and superhuman warriors can fly through a city at impossible velocity. Regardless of how detailed the rendering is, though, something about CGI always feels off. Character movements don’t naturally connect with physical spaces, and actors are clearly flailing against the air as their physical bodies are zipped around in green warehouses to the result of uncanny weightlessness.

The juxtaposition of old and new can be seen clearly in Ridley Scott’s treatment of his aliens in the original 1979 film versus the more recent Alien Covenant (2017).

Covenant’s chestburster is cute and well-rendered, but doesn’t instill terror

Covenant’s creatures are wet and disgusting, gliding through space in terrifyingly inhuman ways. Alien’s original monsters were certainly stiffer by comparison, limited by the mechanics available to them, but they were more tangible. They existed in the space, their limbs wrapped around a human skull, their wormy head puncturing through a bloody chest. They even breathe, as tiny mechanisms mimic the pulsing of lungs.

The few flaws they have (stiff movement and rubbery skin) are easily concealed with smart framing and curtains of darkness. Actors are able to physically react to their attackers rather than flail aimlessly against a yet-to-be-generated force. They feel more horrifying, more real, more convincing. I will always favor a man in a rubber suit over a meticulously crafted virtual image.

Abstraction Breathes Life

Add a certain level of abstraction, and a man in a felty-furry-feathered suit can be even more convincing. Rowlf the Dog was immediately beloved when he started appearing on The Jimmy Dean Show. His design was simple but expressive.

His live arms allowed a more lifelike performance at the hands of two synchronized puppeteers, and Jimmy Dean could talk to the puppet as if he were a living thing. Viewers and staff alike were fully convinced: Rowlf got more fan mail than Dean, and though Henson was voicing the character with his own mic just out of sight, cue cards were held up, and the boom mic shifted over to Rowlf when he spoke his lines.

Rowlf and his co-star, Jimmy Dean

Genty illustrates his ideas while his marionette rests behind him

This balance of the real and the unreal is often explored with puppets. Jim Henson showcased international puppeteers whose work he was inspired by in Jim Henson Presents the World of Puppetry (1985). In this show, he featured Philippe Genty, a French puppeteer, who, in conversation with Henson, described his philosophy on puppetry while holding a glass to illustrate:

“I think puppetry works on two levels. There is one level which is what we call an intellectual level. We know if we animate this glass.. … that obviously there is someone who is manipulating the glass behind it. … We know it won’t be any more glass, but it will symbolize something else. Now the second approach, and this is the irrational part, …is the fact that this glass also, somewhere, behind in our irrational thought, we keep an archaic memory, where we have all these memories of this animism in all time, where we would believe that there is a soul in a tree or a soul in a stone, and this is still there. And we like to believe somewhere, maybe, after all, that this glass is really moved by itself.”

“It’s alive,” Jim Henson offers.

“It’s alive, yes. And I think this is what is fascinating in this world of puppetry that we appeal to both sides of the psyche.”

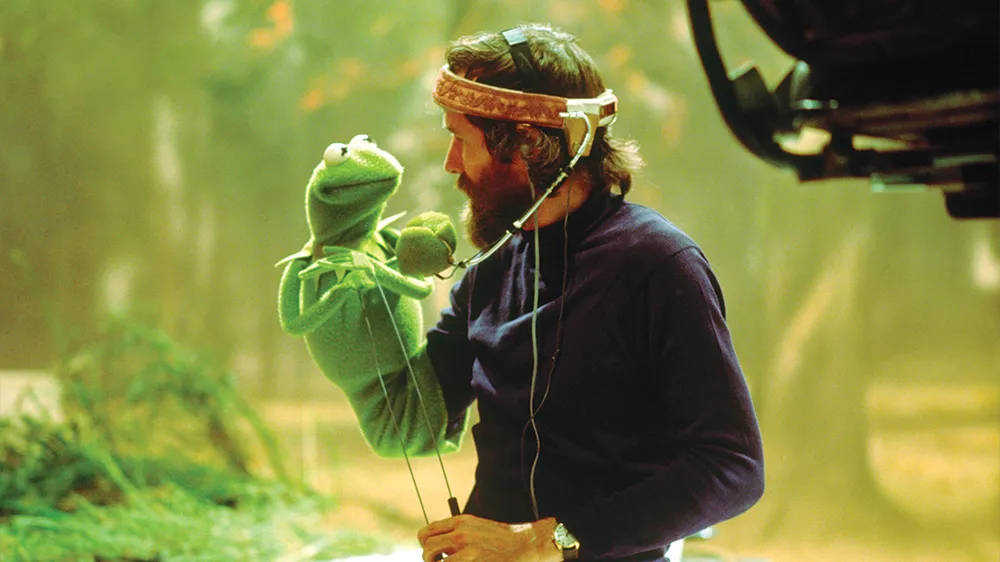

I doubt Jim Henson would use as many words, but he shared similar beliefs. When one of his Muppets wasn’t being actively manipulated, he could toss it aside carelessly, merely a tool of the trade. But when Kermit was on his arm, he was Kermit. When guesting on The Dick Cavett Show, Cavett remarked that it’s “hard to tell where Kermit leaves off and you begin.” Henson simply replied, “Yes, I’ve noticed that too.”

Even directors could be fooled, as they would sometimes give stage directions directly to the Muppet. Audience members would become enraptured by Henson’s performance even as his arm was clearly visible, disappearing into Kermit’s body. It’s an inanimate object, yet capable of life. Cavett put it succinctly: “No matter how much you know about this, it’s completely convincing.”

Kermit would remain Henson’s favorite character to perform

Puppets in the World of the Fantastic

With this innate kind of magic, puppetry is well suited to the world of fantasy. Intellectually, we know the genre to be full of the playfully imagined. At the same time, it’s so mythic, so rooted in cultural traditions across time, it doesn’t feel real per se but true to some facet of the human experience. We can see how puppetry elevates this genre if we again look at Ridley Scott’s work in comparison to Henson’s.

There are a lot of issues with Ridley Scott’s Legend (1985). The theatrical release, in particular, feels like a speedrun through well-known fantasy tropes and the hero’s journey. The speed is probably for the best, though, so we never have to spend too long with the exceedingly dull main character. The lack of clear plotting and the obsessively long takes of unicorns prancing in the forest leads me to believe the entire film was created as revenge for the deleted unicorn scene from his preceding feature, Blade Runner (1982).

Tim Curry’s entire body would be covered for the role of Darkness

It’s not the worst fantasy film, and it certainly is beautiful to look at, but there’s a sense of magic and wonder that simply isn’t achieved in Legend. Costumes and heavy prosthetics, while impressive when captured in a still frame, limited the actors’ expressions to the flapping of their gums. Tim Curry, in the role of Darkness, managed to act his heart out despite five and half hours worth of makeup and three-and-a-half foot prosthetic horns atop his head. He is an oasis in a desert of dry characters.

The sole redeeming scene showcases the delightful Darkness toying with Mia Sara’s Princess Lili as he attempts to destroy her innocence and bring her to his side. Mia Sara almost got to revisit those themes of childhood innocence and looming adulthood when she auditioned for Hensons’s Labyrinth (1986). Though she didn’t get the part, Mia would eventually collaborate with another Henson when she married his son, Brian.

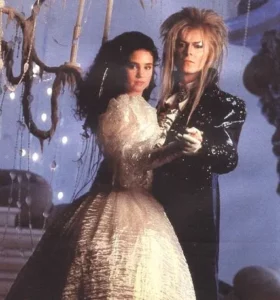

Sarah and Jareth

Jennifer Connelly would instead land the role of Sarah, to be seduced by David Bowie’s Goblin King (every young girl and queer teen’s fantasy). Unfortunately, the film was critically panned at its opening due to a messy script resulting from a too-many-cooks scenario where countless revisions passed between Dennis Lee, Terry Jones, Henson, Laura Phillips, Elaine May and even producer George Lucas.

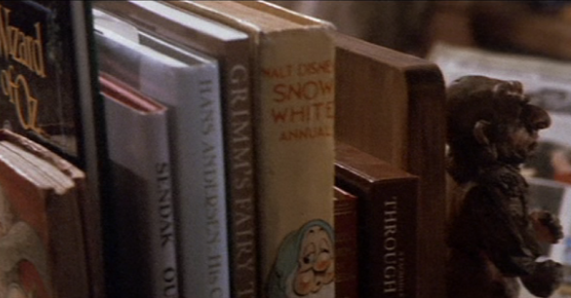

Labyrinth’s beautiful visuals were clearly informed by Henson’s first foray into fantasy, The Dark Crystal (1982). Every visual cue helps to convey the story despite the meandering script. Sarah is clearly torn between her world of play as her childhood bedroom comes to life on this quest to rescue her brother and accepting the world of adulthood. Even Jareth’s pronounced endowment adds to the storytelling as it represents Sarah’s ideal version of adulthood, full of romantic love and playfulness, not crying baby brothers, jobs and responsibilities. And, of course, the puppets amplify this narrative by filling the world with strange and imaginative visuals.

Sarah’s fanciful collection of fairy tales, held up with a small Hoggle bookend

Sarah’s desk with Sir Didymus and a toy maze

a doll of Jareth stands on Sarah’s vanity

Puppetry allows for more malleability than typical props and makeup, particularly with the advancements Henson’s team made with their building of creatures. A performer’s hand can dictate a wide array of movements. Remote-controlled mechanisms further control everything from blinks, raising eyebrows and scrunching of the nose. Hoggle, in particular, was made possible by the collaboration of five performers, one actor inside the suit, while four others stood off to the side to control each look of surprise and anger, perfectly in sync.

In addition to Hoggle, the Labyrinth set was filled to the brim with an assortment of evocative puppets, from as small as a five-inch worm to the largest puppet ever made by Henson’s Creature Shop, the 15-foot Humongous, which was powered by hydraulics while the arms were puppetted remotely. The Helping Hands are perhaps the simplest visually, just human hands arranged to mimic faces, but still required performers to cram together to achieve the multi-handed effect.

The Fireys used the traditional medium of black theatre, which uses a shallow curtain of light to frame the puppets while the performers stand just out of sight, dressed in all black. The medium is updated here, though, as the blackness is chroma-keyed out and replaced with a digital forest for the Fireys to dance in.

the Fireys dance before a digital background

Henson loved to combine the old with the new to create new possibilities. With the world of puppetry opened up, he could create truly fantastic worlds and would continue to do so until his early death in 1990 at the age of 53. John Hurt, who once had a violent puppet alien bursting out of his chest, would go on to befriend a gentler puppet dog as he played the titular character in Henson’s TV series The Storyteller (1987–89). This series integrated live actors, puppets, chroma key shadow puppetry and other special effects that would mark a true synthesis of Henson’s life work. Each episode was a critical darling.

Legacy

With the chokehold of CGI, puppets have widely lost their popularity outside of children’s media (yet even Sesame Street is a shadow of its former self). Despite the fact that the art form was taught in college for decades (Henson himself took a course at the University of Maryland, College Park, though he ended up mostly leading it, having already performed on television somewhat regularly), the “frivolous” medium is now the first to fall to budget cuts. For example, West Virginia University is one of only two schools that offer a major in the subject, and it is still threatening to cut the program without sufficient enrollment. Serious STEM courses are always favored over the arts. But if things continue on and young artists aren’t given the space to flourish, the entertainment industry will completely flounder within a generation.

a young Brian Henson performs some of Labyrinth’s goblins alongside his father

Fortunately, Henson’s children, Lisa, Cheryl, Brian, John and Heather, are still carrying on his work, running the Jim Henson Company and Jim Henson Foundation while simultaneously performing, building and advocating for puppetry. The Creature Shop remains active and just built the puppets for the recent Five Nights at Freddy’s (2023) adaptation. Other studios like Herne Hill Media, the effects house behind Guillermo del Toro’s Cabinet of Curiosities (2022), are also carrying on the mantle, beautifully stitching together practical and VFX to create truly haunting visuals that I’m sure Henson would fully endorse.

All I can hope for in the future is that the fractured, lazy worlds churned out by Marvel will slowly give way to projects that take advantage of the craft that Jim Henson so adored.

ShortHaus Cinema will meet to watch and discuss Jim Henson’s early work next Tuesday, December 5, at 7 p.m.

Much of Henson’s work is available on Kanopy, including his early short film collection, an unfinished cut-paper animation Alexander the Grape (1965), his Oscar-nominated experimental short Time Piece (1965), Storyteller and its spin-off Greek Myths (1991), and a delightful environmental-themed short made for the failed Jim Henson Hour called Song of the Cloud Forest (1989). Additionally, Jim Henson Presents the World of Puppetry (1985) offers wonderful insights into all different kinds of puppetry from international creators.

The Muppets are available in all their glory across our Blu-ray and DVD collections, as well as the fantastic creature features of The Dark Crystal and Labyrinth.