There’s a really neat literary concept I’ve been thinking about frequently, and I’d like to share it with you as a means to discuss Roshani Chokshi’s novel, The Last Tale of the Flower Bride.

When I read or consume media, I’m constantly seeking connections between one voice and the next. How can I link the stories I enjoy in leisure with the important stories I try to center in my academics? Where does the inspiration for these narratives come from, and is it even possible to accurately trace the “origins” for many of our common literary expectations?

In short, no, it’s not. I can tell from experience that untangling the threads of narrative throughout human history is… complicated and made exponentially more difficult by the myriad languages, mythological systems, religious structures, narrative forms and other contextual complications present throughout human history. However, there are commonalities across the spectrum of humanity where, even with disparate origins, similarities serve to link times, cultures or otherwise independent narratives with each other. Welcome to a concept referred to as “the Cauldron of Story.”

In short, no, it’s not. I can tell from experience that untangling the threads of narrative throughout human history is… complicated and made exponentially more difficult by the myriad languages, mythological systems, religious structures, narrative forms and other contextual complications present throughout human history. However, there are commonalities across the spectrum of humanity where, even with disparate origins, similarities serve to link times, cultures or otherwise independent narratives with each other. Welcome to a concept referred to as “the Cauldron of Story.”

Attributed to J.R.R. Tolkien, yes, that Tolkien, the Cauldron of Story is a theoretical “pot of soup” simmering away in the collective imaginations of all people, composed of all the major stories ever told. In a post-Marvel world, this concept has become a lot easier to explain. It’s like the multiverse; Spider-Man is Spider-Man is Spider-Man… but sometimes he’s Peter Parker, and sometimes he’s Miles Morales. But, by the nature of a multiverse, there are pre-determined archetypes that new authors and creators can use to quickly gain audience recognition. Following the Spider-Man allegory, no matter which version of the character is on-screen, audiences have certain expectations because of the character’s archetype; i.e., he’s usually one of the youngest Avengers, incredibly intelligent, etc., but the details can change to make commentary on different aspects of the story.

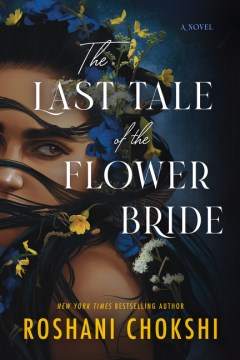

When I listened to The Last Tale of the Flower Bride by Roshani Chokshi, I knew I had to speak about this concept to review the book. The book itself was lyrical and compelling. Chokshi is not a debut novelist seeking her sea-legs, but an experienced multi-genre and age-defying author, and her skill is evident from the outset. What she has done with Flower Bride, her first novel aimed specifically at adult audiences, is craft a brilliant narrative from one of those myths bubbling away in the Cauldron of Story. Even when I could sense the pattern unfolding around me as I listened, the areas Chokshi seemed to emphasize as important (the disillusionment of love; sacrificing yourself for love) were unique to a mythological history that has been in play for hundreds of years.

“The Last Tale of the Flower Bride” by Roshani Chokshi

The Last Tale of the Flower Bride by Roshani Chokshi

Genres: Fantasy Fiction; Modern Mythology; Fairy Tales Retold

First Released: 2023

Part of a Series: No

Call Number: FANTASY CHOKSHI

Eyan’s Rating: 5/5

For Fans of: Mexican Gothic by Sylvia Moreno-Garcia; Diane Setterfield; The Inheritance of Orquídea Divinia by Zoraida Córdova

Summary

Once upon a time, a man who believed in fairy tales married a beautiful, mysterious woman named Indigo Maxwell-Casteñada. He was a scholar of myths. She was an heiress to a fortune. They exchanged gifts and stories and believed they would live happily ever after—and in exchange for her love, Indigo extracted a promise: that her bridegroom would never pry into her past. But when Indigo learns that her estranged aunt is dying and the couple is forced to return to her childhood home, the House of Dreams, the bridegroom will soon find himself unable to resist. Within the crumbling manor’s extravagant rooms and musty halls, there lurks the shadow of another girl: Azure, Indigo’s dearest childhood friend who suddenly disappeared. As the house slowly reveals his wife’s secrets, the bridegroom will be forced to choose between reality and fantasy, even if doing so threatens to destroy their marriage… or their lives.

Eyan’s Review

Told in alternating modern-day and past-tense chapters, the story unfolds in a creeping, non-linear fashion, which adds to the overall feeling of discomfort and insecurity throughout. The bridegroom, the nameless male character voiced by Steve West, comes from the modern day. His experiences with his mysterious and lovely wife, Indigo, flavor his experiences. But his role as an academic, a student of fairy tales, opens the door to an entirely new world of possibilities. His wife has extracted one promise from him prior to their marriage, and it’s one that any fairy tale scholar would recognize immediately: do not pry, for you will not like what you find. Enter the Cauldron of Story.

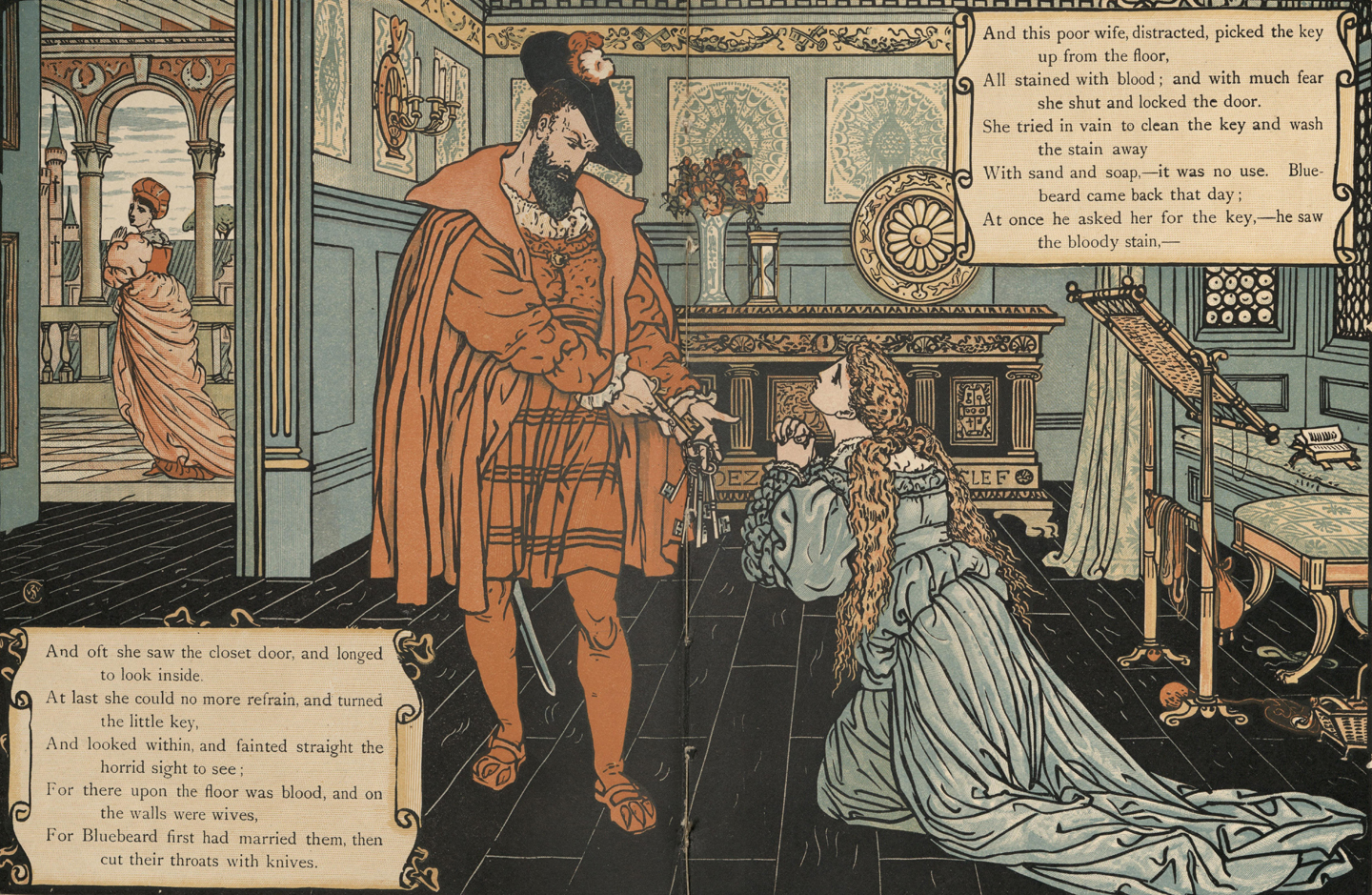

There are two competing elements at play. The first, the mysterious spouse with a secretive past, evokes images of Bluebeard and his many slain wives. Bluebeard is so ubiquitous with this story arc that even his name has been recognized by the Merriam-Webster dictionary as “a man who marries and kills one wife after another.” Certainly, The House of Dreams, with all its secrets, mysteries and locked doors, plays on those expectations.

The second element is more complicated because it’s not the core of every fairy tale, but it is at the center of enough romances for both the bridegroom and the audience to wonder if a solution might exist: true love breaks the curse.

If he truly loves Indigo, as the bridegroom wonders to himself, wouldn’t he try to free her from whatever curse causes her secrecy? True love as a concept originated in the literature of the medieval period, but it looks very different than how we might describe love today. Regardless, the structures by which other authors have examined these narratives exist, and it’s clear that Chokshi was aware of these inspirations enough to keep their flavor in her own story-soup.

Finally, flower brides themselves have existed in the literature of the European tradition for a very long time. Dating back to the 11th century in written form, but traced back generations further in the oral tradition, the Welsh Mabinogion includes a great deal of early British/Celtic mythology.

One such tale introduces Blodeuwedd, a woman whose name literally translates to “flower-face.” In this tale, the Welsh hero Lleu Llaw Gyffes is cursed by his mother to prevent his marriage to a human woman. Instead, the great magicians Math and Gwydion craft a woman from broom, meadowsweet, and oak flowers to be his bride.

Blodeuwedd by Christopher Williams (1930)

Blodeuwedd, despite being literally created to be Lleu Llaw’s wife, is not a good partner. She immediately has an affair and seeks to learn the secret vulnerabilities of her husband, who is immune to most types of harm. Ultimately, she is transformed into an owl for her treachery, which will prevent her from showing her face in the light of day ever after—a significant punishment.

Of course, other romance narratives also use flowers to convey meaning, namely the Greek myth of Hades, Lord of the Underworld, and his wife Persephone, Goddess of Spring. In that myth, Persephone, the literal embodiment of the seasons and harvest, is picking flowers when first seen by Hades. Her marriage to Hades results in the seasons as we know them: for the winter half of the year, she resides in the underworld with her husband, and in the spring, she returns to the overworld to bring new life to the world.

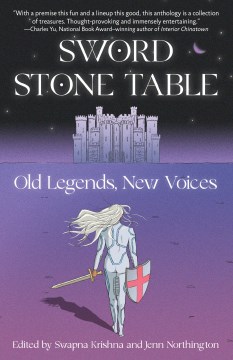

So, all of these different myths are simmering together in the Cauldron of Story, and I am absolutely certain that Chokshi is familiar with all of these tales. The Mabinogion, while not specifically Arthurian, overlaps with Arthurian literature nevertheless; I had to study it during my MA program. I believe Chokshi is at least tangentially aware of this literary history because of her inclusion in one of my favorite anthologies: Sword Stone Table: Old Legends, New Voices. This book, a collection of Arthurian myths retold by various and diverse authors, includes one from Chokshi, which I use in the classes I teach. Chokshi’s story gives voice and agency to one of the sorely maligned women in the medieval tradition, Elaine, who, through magical deception, bears Lancelot’s child.

Chokshi’s reworking of Elaine’s story was powerful and poignant, giving agency to a character who existed on the page, to date, as a means to further Lancelot’s story. She bears the child Galahad, the perfect Grail Knight, the only knight more worthy than his father. I highly recommend reading Chokshi’s version of the tale, called “Passing Fair and Young,” which is the second chapter in Sword Stone Table. The connections between the two stories are, perhaps, vague and insubstantial. However, it’s clear to me that Chokshi’s characters are always incredibly three-dimensional and well-developed; they have real depth to them. Her reclamation of feminine voices in the Arthurian canon, as well as the deft way she manipulates expectations with flower bride mythology, is potent and important, and I definitely recommend both The Last Tale of the Flower Bride and “Passing Fair and Young,” if not the entire Sword Stone Table anthology.

Chokshi has a clear and profound narrative voice, and I find myself consistently enraptured by the subtle layers of her storytelling. From the surface-level enjoyment of a good story to the hours spent analyzing textual patterns, I think just about anyone can find value in Roshani Chokshi’s writings, and I highly recommend everyone to go find her on the shelf.