Military pension records can be a rich resource for genealogists. They offer valuable insight to military service, dates and locations of battles, injuries and maladies which required hospital treatment and solid informational family data. Shuffled in these pension records are clues which can point you to new records and resources.

I have been updating the walking tour talking points for Boardman Cemetery, and requested a military pension for Robert Hale Strong, a Civil War veteran born in 1842 just a few miles from the library. A collection of his wartime recollections were compiled in the 1920s, and were published in 1961 under the title A Yankee Private’s Civil War. The book chronicles Strong’s time in the 105th Illinois Infantry, as well as personal recollections of his parents, siblings and their family home. The Strong family home site stood on Royce Road, with the house and spring located on property owned by the DuPage River Trail and the other section composed of the Walnut Ridge subdivision.

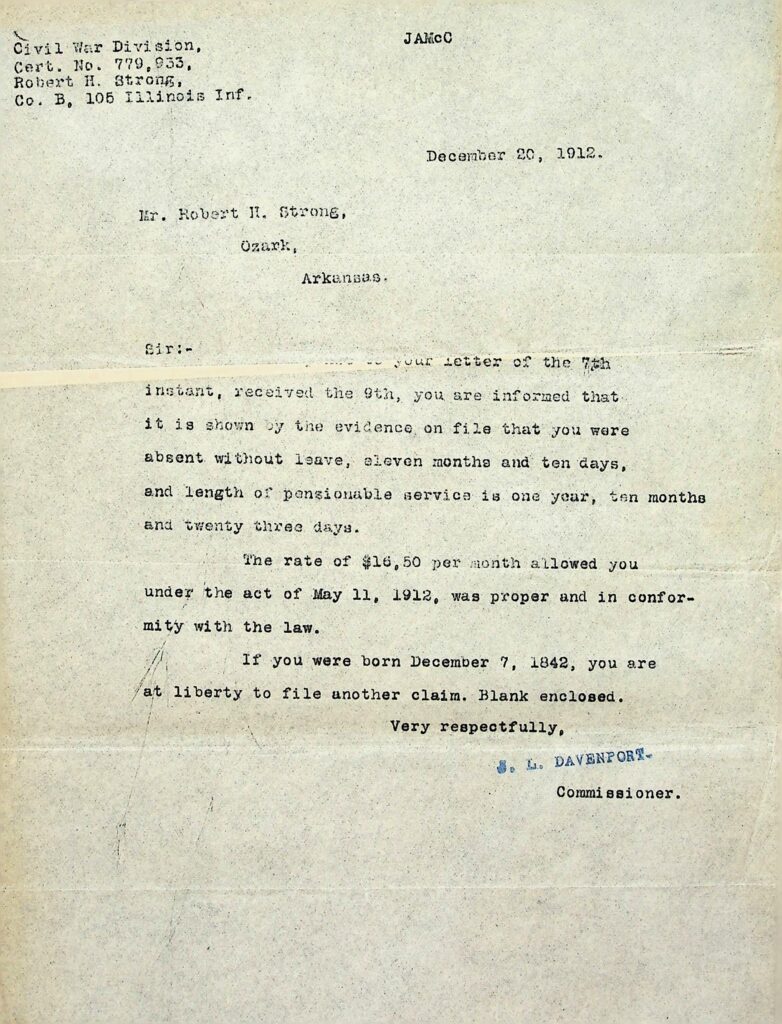

The researchers and volunteers at the Bolingbrook Historic Preservation Commission have spent years compiling genealogical data on the Strong family. I looked over our list of references and noticed the bulk of our military information for Robert Hale Strong is cited from his personal memoir and does not contain any documents relating to his Union Veteran Civil War pension record. I ordered the file, along with a few other odds and ends I had on my research list. In the review of the roughly 125 pages of his disability pension file, Robert consistently lobbies for an increase in his pension due to the length of his time in the service. His pension increases are rejected multiple times, on account of a desertion charge for which he was later court-martialed.

233

Woah.

A court martial is a judicial court for trying members of the armed services accused of offenses against military law. The Continental Congress first authorized the use of courts-martial in 1775, and documentation of these special records are available by request from the National Archives.

A few genealogy websites estimate that around 80,000 court-martials were held during the Civil War. Paperless Archives states “The charges found in these documents range from murder, physical assault, spying, treason, desertion, embezzlement, theft, conduct unbecoming an officer and a gentleman, disorderly conduct, disobedience of orders, disloyal statements, drunkenness, and various misdemeanors and infractions of military rules.” Desertion was a common offense, and I’ve seen it in other Civil War service file records and accounts. A few days off here and there were understandable, but more than a year? That is excessive, and I’ve rarely encountered that period of time during my years of research.

This desertion and court martial is not chronicled in A Yankee Private’s Civil War. The missing year is not well documented in the papers I currently have on file. Civil War court martial cases do require some legwork to acquire, as you would usually need to visit the National Archives in Washington D.C. to request and view copies. Fortunately, I made arrangements with Brian Rhinehart from CivilWarRecords.com to pick up the court martial for me.

A few weeks later, the court-martial arrived in my email. The court case was short, about seventeen hand-written pages, with most of the early portions listing names and ranks of individuals leading the proceedings. The real interesting information starts to appear on the ninth page, where Robert Hale Strong’s superior officers begin to divulge details of his desertion.

“On the march from Frankfort, KY, he [Robert Hale Strong] stated that he could not go on farther. The captain told him to try and keep up, and if he could not he would have to fall behind. It was on the 26th of October. 1st Day out. Have understood that they followed the regiment for several days, were captured and paroled. They reported at Gainesville, and were sent to Camp Chase. They left Camp Chase without a furlough. I know that he left Will County Illinois for parts unknown. I received a furlough on the 16th of September 1863. He came home, while I was at home. He said he wanted to join his regiment. On the 29th of September, he reported himself to me, and asked to be sent to the regiment. I received a letter on the 1st February 1863 from Mrs. Strong his mother stating the accused wanted to return to the regiment provided he could return to the company and not be treated as a deserter. I wrote her he would have to be tried by Court Martial.”

In his defense, Robert Hale Strong submitted a written address to the court stating he was ‘guilty as charged’ but attributed his defense as being ill with a lame ankle, and after being unable to walk was captured and paroled by confederate troops. After reporting to Camp Chase in Ohio, Strong was told by the camp adjutant that “he could not give me a furlough, but said if he was in my place he would go home and return when called for. I did so, and had been home some four weeks when to my surprise I was advertised in one of our county papers as a deserter.”

Not wishing to report back as a deserter, Robert Hale Strong stated he left the state of Illinois for Canada, and was there on the 28th of March when he received news of President Abraham Lincoln’s Proclamation 111, which granted amnesty to union soldiers who had deserted during the course of their service. Short on cash and unable to return promptly to military service, Strong stated he bounced between Canada, Delaware, and Wisconsin until September 28, 1863 when he reported to Lieutenant Scott at Naperville and requested amnesty and a return to military life stating he would be “a good boy to my company and regiment, where I know by bitter experience that I will remain with it until I am honorably discharged.”

You can read the original pages here:

In his account, Robert Hale Strong spends a few pages documenting his time in Bowling Green and the march to Frankfort, most of his account details guard duty, lack of food and the meager shelter of his assigned tent. He also includes descriptions of the high death toll and the growing cemeteries established to accommodate his fallen comrades. No mention of the lame ankle, his desertion, or the time he spent in and around Canada. Then the narrative abruptly time jumps from October 1862 to the autumn of 1863, the time from in which his court martial is over and he has rejoined his unit at Fort Negley near Nashville, Tennessee. From the documents included in his file, it does not appear he performed the six months hard labor set down on his court martial. This may have boiled down to General Sherman’s need for a legion of able bodied men to march from Atlanta to Savannah, a bold military stroke to break down the confederate war effort. After all, why assign a healthy young man to hard labor on a government project when you need able bodied men for a dangerous military expedition?

Between the lines of this written account, we can place ourselves in the mind and body of an overwhelmed 19-year-old farm boy, with little experience of the world and wholly unprepared for the challenges of military service. It is even more poignant that it is his mother, Caroline Willey Strong, wrote the government for clemency, wholly invested in the health and well-being of one of her few surviving children. The connection between Caroline and her son is palpable, as all the entries in Robert’s book A Yankee Private’s Civil War are addressed to her. His father, Robert Sr., remains a distant and remote figure in the narrative, with only two scant mentions at the beginning and end of the book.

This court-martial information does make us question why Robert Hale Strong was fighting for a pension increase when he submitted a guilty plea to desertion and was clearly not rendering military service for his missing year? It is possible he thought his honorable discharge and presidential amnesty would make up for that lost year, and he was uncertain on how the government would calculate his pension. It is also possible he simply needed more financial support provided by a more robust pension disbursement. More research and documentation would be needed to explore his motivations.

Given the high volume of desertions and an amnesty proclamation, you might ask ‘Are there court martial records online?’ The answer is: not really.

The National Archives in Washington DC has an index of Civil War court-martial records, however, you will need to visit the archives in-person or pay a researcher to acquire the records on your behalf. One online collection of records entitled Proceedings of U.S. Army Courts-Martial and Military Commissions of Union Soldiers Executed by U.S. Military Authorities, 1861-1866 is available for free on FamilySearch. Fold3 hosts a robust collection entitled US, Navy Courts Martial Records, 1799-1867, which you can access for free at a FamilySearch Center or from home with with your Fountaindale Public Library card.

Court-martials are not limited to Union troops. The Confederate states also had high volume of deserters and those court-martials as well as military pension records are held on a state level. The United States Federal Government does not house or maintain copies for researchers. For example, the Missouri State Archives houses court martial papers, as well as registers for military prisoners, punishment registers and other under-researched documents.

If you are interested in learning more about genealogy topics, please join us for our free virtual lectures. These are open to everyone, and library cards are not required! If you have any questions or need help with registration, please call 630.685.4176 or email ddudek@fountaindale.org.

Here are our upcoming programs and registration information:

- Wednesday, September 27, 11 a.m. CST: Wisconsin Historical Society Collections & Services

- Wednesday, October 11, 7 p.m. CST: Why Was Grandma So Mean?

- Monday, October 16, 7 p.m. CST: Spiritualism & Mourning in Victorian America

- Wednesday, October 25, 11 a.m. CST: Let’s Meet DNA Painter!

- Wednesday, November 8, 7 p.m. CST: Using Fold3 To Your Advantage

- Wednesday, November 15, 11 a.m. CST: Prisoners: Missing & Dead

A full list of our upcoming 2024 Genealogy Club events will be available in October! We look forward to having you with us for an action-packed year of great programs and events!

See You At The Library!

Debra