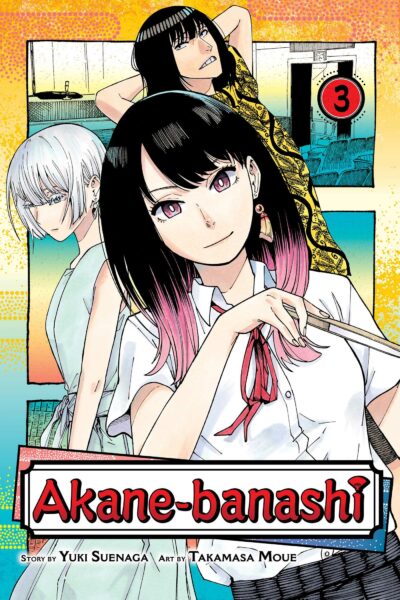

Short version: Akane-banashi (roughly “Akane’s Story”) is a serialized manga series that creatively blends sports manga tropes into a story about rakugo, a Japanese storytelling art that emphasizes the performer’s conversation skills. Excellent art from illustrator Takamasa Moue conveys the titular Akane’s affability and technical expertise at her craft in wonderfully creative ways, while author Yuki Suenaga weaves a compelling story about an artistic genius learning to be a better human. The various translators working on this project impressively adapt the wordplay of this uniquely Japanese art form into English. Everyone involved with bringing this story to life and into the English language is bringing their “A” game, resulting in an absolute must-read for manga fans, and a good, grounded story to start with if you’re new to the medium.

Find copies of Akane-banashi in our catalog

In a previous blog post, I alluded to the output of Weekly Shonen Jump and its related magazines and apps, and how a certain genre of story tends to dominate, especially when discussing international success. Dragon Ball Z, Naruto, One Piece and My Hero Academia; all of these popular and critically acclaimed titles fall under the same genre: battle manga.

Battle manga, or fighting manga, is a subgenre of action comics. The genre tends to have a lot in common with Chinese wushu films and American superhero media, yet still has its own genre conventions, often focusing on hard work, rivalries, secret fighting techniques and the power of friendship.

A close cousin of the battle manga genre is sports manga, and it’s easy to see why. Most of the attributes I listed fit in a story about sports just as readily as a story about fighting the force of evil. In contrast, it’s probably a little harder to imagine how those same genre conventions fit into a story about sitting on a pillow and telling funny stories.

Nevertheless, manga authors have come up with wilder ideas. Yu-Gi-Oh! famously incorporates battle manga tropes into a trading card game, while Hikaru no Go is, for all intents and purposes, a sports manga, albeit one that focuses on the strategy board game Go. And so Akane-banashi continues this grand tradition of taking the comfortably familiar genre conventions of battle and sports manga and shoving them into the environment you would least expect. And it has done so to great success!

with over 100 serialized chapters collected in over 12 volumes, about half of which have been translated into English, Akane-banashi has become a staple of Weekly Shonen Jump’s lineup. The series has received critical acclaim here in the US, being included in the New York Public Library’s “Best Books for Teens in 2023” and the Young Adult Library Services Association’s 2024 list of Great Graphic Novels for Teens.

So today, I’d like to honor Suenaga and Moue’s accomplishment by taking a look at Akane-banashi as a whole, and hopefully introduce some new readers to one of the most intriguing manga I’ve read in a long time.

Akane always admired her father’s art. Shinta Arakawa was a rakugoka, a rakugo performer. Rakugo is a storytelling art similar to a one-man show but with key differences in presentation. The goal is to sit formally in the center of the stage and convey character and emotion with nothing more than changes in pitch and tone, a slight turn of the head, hand gestures and, at most, a folding fan and a handkerchief as props. It’s all about the art of conversation, and getting the most out of the limitations imposed upon the artist.

Shinta Arakawa was a rakugoka. A talented and respected one, even though he hadn’t yet reached the upper echelons of the art form. However, an incident occurred that led to the mass expulsion of several students from the Arakawa school; and Akane’s father was among those cast out. As a result, Akane seeks the teachings of Shinta’s master, Shiguma Arakawa (students take on the master’s surname). We catch up with Akane years later, as she’s on the verge of graduating high school and becoming officially recognized as Shiguma’s pupil.

Akane is talented but hot-headed and slightly self-absorbed. She’s the sort of protagonist who is already an expert in the field that the series is ostensibly about, but lacks an understanding of nuance and the more emotional aspects of the art. As her fellow pupil puts it, she throws 90 mph pitches far outside the strike zone. As such, her journey is less about improving her art and more about learning to be a more considerate and thoughtful person. In this way, we see that the series is really about respect.

Background characters receive loving attention from artist Takamasa Moue, emphasizing one of the core messages of the story; that the common people are worth honoring. In the audience of Akane and other rakugoka’s performances, we see people often overlooked in teen manga: elderly people, overweight people and even visibly queer people. Our main cast is still predominantly the kind of thin and pretty people you’re used to in anime, but they share a world with a fairly diverse cast of supporting characters.

Though rakugo is a performing art, the story develops in ways that mirror sports and battle manga. In the third volume, an amateur rakugo tournament is held, and Akane’s eventual rivals are introduced. These include Karashi, a college student and comedian who approaches rakugo with a disdain for its history and aims to drag the art kicking and screaming into the 21st century, and Hikaru, my favorite character.

As a popular voice actress, Hikaru comes into the world of rakugo with a dedicated fanbase and plenty of acting skill, but little understanding of how to work within the limitations rakugo imposes upon the performer. She’s an expert at conveying emotion but lacks skill in the art of conversation. Despite her fame, Hikaru seems humble and thoughtful of others. All of these traits seem to be setting her up as someone whose strengths and flaws are the opposite of Akane’s, but the truth may be more complicated.

Character designs are highly effective, with Akane’s bright pink tips conveying her fiery personality and willingness to bend the rules as much as she can get away with. Hikaru’s blues and whites contrast Akane’s reds and blacks to further emphasize their rivalry, and Karashi’s almost Joker-like smile makes him stand out from the crowd, which he clearly strives to do. Effective shading and framing make even somewhat silly character designs look intimidating, and some designs are outright cartoony yet still feel like a cohesive part of the manga’s world.

And I can’t move on from talking about the art without bringing up the creative use of word balloons. In this manga, rakugoka have differently shaped word balloons for each character they’re portraying in their performance. Often times a difference in skill level is conveyed by how distinct those word balloons are from each other. There are other little details regarding how performers distinguish their characters, so be sure to keep an eye out for them while you’re reading!

In the early volumes, Akane’s supporting cast consists predominantly of her fellow pupils. Each expands her understanding of rakugo in unique ways, such as Kyoji teaching her to be more considerate of her audience or Koguma emphasizing the historical aspect of the art. Not only does this help Akane improve as an artist and a person, but it also portrays rakugo as a rich and complex art with a deep history.

Akane’s relationship with her fellow pupils is where some intriguing translation choices are made. In several parts of the story, the translators choose to lean into the Japanese origins of rakugo and leave some terms untranslated, though with quick explanations of their meaning. The most recurring example of this is Akane referring to her fellow pupils as “Ani-san,” which is essentially a way of calling them “brothers.”

This can make for a mouthful when the term is used as a suffix, such as when Akane addresses Kyoji as “Kyoji-ani-san.” However, much like the turn-based RPG Yakuza: Like a Dragon, which makes the same creative choice, this adds a unique texture to the story and the characters’ relationships. Rakugo and yakuza may have rough equivalents in other cultures across the globe, but the devil’s in the details, and the details of these two subcultures are distinctly Japanese.

Now, I don’t want to make the mistake of overly exoticizing Japan, as so many writers have done in the past and continue to do today. That said, it can’t be denied that for those outside of Japan, part of the appeal of anime, manga and Japanese video games is the fact that they come from a distinct culture that’s different from the audience’s own. So it makes sense to lean into that aspect sometimes, and I think a story about rakugo is the perfect place to do so.

On the topic of translation, it’s a tall order to translate any sort of comedy series from one language to another. As you might suspect, given the nature of rakugo, there’s a lot of wordplay, puns and idioms, which is a veritable minefield for those who translate and localize foreign language media. Pacing is equally difficult; anyone who has seen English-translated lyrics of a J-pop song can tell you that Japanese and English have two very different rhythms. In short, this is a challenging series to translate, which makes it all the more impressive that the translators knock it out of the park.

I can’t speak to the exact accuracy of the translation, and the idea of “accuracy” in this context is more subjective than you may think. What I do know is that, during the character’s rakugo performances, the jokes land, the drama tugs at the heartstrings, and the horror is disturbing. Much of this is thanks to Takamasa Moue’s evocative art, to be sure, but the translators are more than pulling their weight.

Dialogue during conversations between characters, meanwhile, feels natural and authentic. The characters in their teens and 20s sometimes use American English slang, which is often a bit of a gamble when it comes to anime and manga translations. Do it wrong, and your translation ages like stale bread. However, in this case, the translators are appropriately restrained, in my opinion.

This series is a smooth and easy read but still emotionally impactful. Everyone involved with this publication brought their best, and the results are fantastic. Manga and anime aficionados who appreciate the art of translation in and of itself absolutely need to give this title a read.

On every level, Akane-banashi swept me off my feet. A great story, compelling characters, a stellar translation and localization, expressive art and creative use of sports and battle manga tropes in a story about the performing arts results in a series that has enough familiar elements to keep the audience grounded while bringing those elements into a brand new environment. This is an amazingly unique series among Weekly Shonen Jumps’s current offerings, and our consortium is proud to be able to offer the collected volumes to our patrons. This series hits that sweet spot between the familiar and the new, and that’s where many of the most entertaining stories live. I would definitely rank Akane-banashi among them.