The next featured ShortHaus Cinema director is actually a pair of directors, Cristobal León and Joaquín Cociña, a joint team of stop-motion animators from Chile. We’ll soon be celebrating Hispanic Heritage Month, so I wanted to select a series of Spanish-language films to mark the occasion. And because I love anything weird, I chose the strangest filmmakers I could find on Kanopy.

At the same time that León and Cociña are attempting to reimagine history with their stop-motion animation, they are changing the course of Chilean animation history. Though they started out with a rudimentary understanding of the medium, they have been developing and expanding their techniques to tell complex stories. At the center of each story is the idea of creation, making art, drawing and showing the process behind it.

Seamless Standards

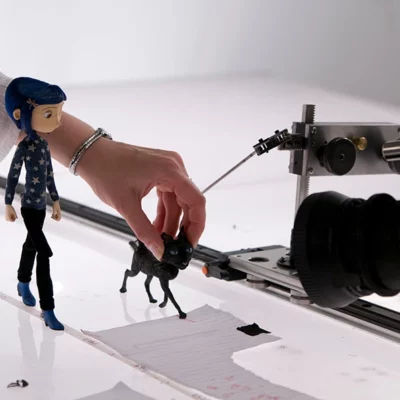

In the West, we’re used to seeing extremely well-polished stop-motion animation. When we look at behind-the-scenes footage of beloved films like Nightmare Before Christmas (1993) or Coraline (2009), we’re in awe of the sheer time and manpower it takes to create such beautifully subtle movements over a feature-length runtime.

If shooting at the standard frame rate of 24 frames per second, 1440 individual photographs would need to be taken for just one minute of animation. Many stop-motion animators drop that rate when smooth action shots aren’t required, but even 12 frames per second would require 720 photographs per minute of animation.

Every step a figure takes, every swish of the arm, every change in facial expression has to be carefully shifted frame by frame. For dynamic movement, figures need to be held up with stands and wire to hold them up mid-jump, but then those guides are carefully wiped away in post-production. The result is a beautifully smooth animation that gives none of its process away.

behind the scenes of Coraline

This process, though tedious, is particularly well suited for the horror genre, as it lets artists conjure up imagery far too difficult to puppet via a man in a rubber suit. King Kong (1933), which I mentioned in context with the work of Alison Maclean, set the standard early on with its creature effects.

Ray Harryhausen was then heavily inspired to develop his own animation techniques after seeing the film. I recently thrifted a VHS of It Came from Beneath the Sea (1955), and watching those carefully animated tentacles attack San Francisco is an absolute delight.

But as smooth as stop-motion can be, there’s always something inhuman about the jagged movements. But that can actually help add to the uncanny nature of horror creatures. For example, Basket Case (1982) used stop-motion to animate the undeveloped conjoined twin far less elegantly but more horrifyingly. The awkwardness that Belial Bradley moves with makes him appear much less human and condemns him to the uncanny valley.

from Basket Case

from La Casa Lobo

Thematically, León and Cociña fit very well in this tradition of stop-motion horror, consistently creating uncanny and unsettling imagery in their work. Regardless, the duo still found issues with the medium. In a conversation with LatinX in Animation, Joaquín Cociña said,

“There’s this myth between animators that you suffer during the process and you have to work so much… and you’re a patient human being because you spend so much time working in a piece but actually we, in the landscape of animators, we are sort of like inpatient, brutal human beings.”

That brutality isn’t referencing the subject matter (though it often is quite brutal), but the duo’s use of rough materiality in their work. Despite claymation also being called plasticine animation, the medium is just not plastic enough for the duo.

Plasticity in art refers to the method of leaving traces of your technique in the final product and adding to the work itself. For example, a painting has visible brushstrokes, or a sculpture has chisel marks that aren’t buffed away, and the artist is still present in what remains in the final work. This helps engage with the viewer as a fellow creative. As artists, León and Cociña are very familiar with this idea.

A Drawn Out Start

León and Cociña met while working on their bachelor’s degrees at Universidad Católica de Chile, but they didn’t become friends until they started collaborating on their first project, Lucía (2007). From a cursory watch, Lucía feels haunting. It’s the story of a young girl narrating her unsettling experiences in a whispered tone while the bedroom around her disassembles. However, the impetus for the project was less focused on the subject and more interested in playing with the process of drawing.

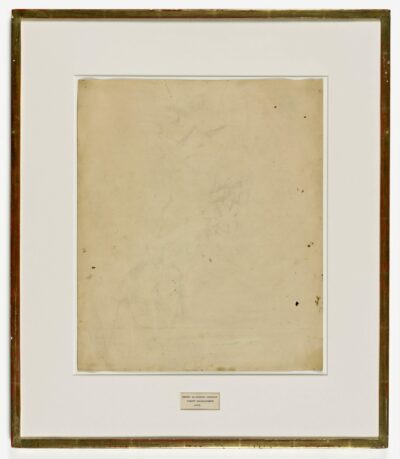

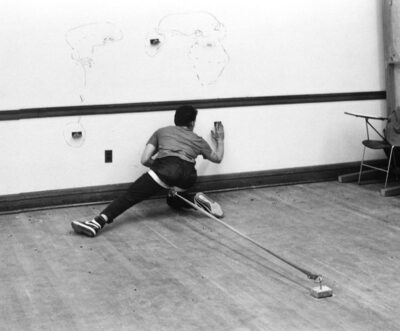

Drawing is such a fundamental part of art that it’s almost a rite of passage for emerging artists to find a way to dissect and reimagine it. Robert Rauschenberg famously displayed an erased de Kooning drawing as his own work, the process of erasing the work being transformative enough. Carolee Schneemann and Matthew Barney used restraints to hold themselves back and limit their movements while they made drawings.

Robert Rauschenberg, Erased de Kooning Drawing, 1953

Matthew Barney, Drawing Restraint 5, 1989

For León and Cociña, their version of this was to record the process of drawing and erasing as it happened over time. Rather than shooting a continuous video to record the act, as Schneemann and Barney had done before them, they chose to integrate the process into stop-motion. By capturing photos in between every line drawn, the artists were able to capture the drawing coming to life. The end result is then a short stop-motion film with highly stylized imagery.

Lucía sits in a chair and screams, the history of her footsteps seen in the panel to her left

As the titular Lucía is drawn onto the wall, her body forms from graphic black lines of charcoal. But the messiness of charcoal refuses erasure, so a large gray smear appears where her body once was. As she moves across the wall, scuff marks appear behind her as her body is wiped away with every step. With every new frame, the remnants of the previous frames remain.

This is plasticity—the method of creation constantly revealing itself. The more the artists draw, the more the walls are lost to dark, dusty smudges, and the room itself has to descend into messy chaos as furniture is spun around, frame by frame, and breaks apart.

the opening shot of Luis

Luis (2008) was the sequel to Lucía and takes the creation and destruction to a new level. Instead of walking into a neat and tidy room, the room we’re faced with in Luis is already covered in charcoal across every inch of wall and ceiling. The room is also already trashed, stuffing pulled from the couch cushions, shelves falling away from the desk, furniture shattered to pieces. The only clean space to be seen are the empty white rectangles betraying the location of formerly hung paintings fallen away.

As the short goes on, time progresses narratively, the young Luis now telling his side of the story in his relationship to Lucía. Simultaneously, time in the physical world regresses: paintings slowly return to the wall, the feathers slink back into the couch cushions, and a broken vase stitches itself back together, wrongly, just broken shards piled against one another with jagged edges exposed. With this second short, León and Cociña expand upon initial drawings by manipulating time, playing more in the medium of film and video.

The Making is the Art

La Casa Lobo (The Wolf House) (2018) takes those techniques and polishes them to a grotesque point. León and Cociña had an idea for their first feature film but knew their previous shorts were not proof of concept enough to get large-scale funding for the project. The duo started working on the project in their own studio, but after some time working, they realized the studio itself often made for a more interesting product than the 10–20 seconds of stop-motion footage they were producing every day. With this realization, they had the idea to set up workshops so that the public could see the studio as it grew and evolved over the production, thus engaging the public fully in the process of making.

Joaquín Cociña (left) and Cristobal León (right) hard at work

With that idea in mind, the duo began applying for grants and residencies, setting up shop in various galleries across Chile and Europe, working for a few months at a time before packing up and moving on. With such a disparate shooting schedule, the duo needed a few guidelines in place to keep the aesthetic vision cohesive across the numerous locations and came up with a list of 10 filmmaking rules. I won’t go over all of them here, but the duo discusses these rules more in an interview available on the DVD release of the film.

Here are a few points I found most interesting:

4. There is no fade to black

5. The movie is a long sequence shot

8. The camera never stands still between frames

10. It is a workshop, not a film set

Although these rules helped organize and speed up filmmaking, they also had intentional aesthetic results. With no traditional transitions or hard cuts, the film takes on a nightmarish quality as scenes bleed over from one to the next with only dream logic piecing them together. While rule number eight helped them not to worry about the camera shifting between frames, the constant movement resulted in vibrating instability and a consistent unnerving feeling throughout the film. With the focus on a workshop mentality, wires and stands that would normally be cleaned away in post were left, showing the seams of the process.

wires can be seen faintly to the right of Maria as her body forms

A face can be drawn on the wall, frame by frame, each line quickly built up in charcoal and drippy paint. Then that same face will slide across the wall, down to the floor and onto a three-dimensional form, a doll you expect to then come to life. But the face and limbs just slip off again. Nothing is permanent.

Each hasty drawing and papier-mâché sculpture is ever-changing, constantly reminding you how it’s made, with shoddy materials showing through. In one scene, the beautiful Maria is slowly built up with layer upon layer of cheap masking tape. We watch this version of her be created, the whole time being held up with wires. Again, this is plasticity.

Drawing from History

León and Cociña are constantly referencing history just as history is being made. La Casa Lobo (which references the history of the German settlement Colonia Dignidad in Chile) made film history as the first feature-length stop-motion film to come out of Chile.

And while they were making history with their film work, historical events were happening in Chile. After social uprisings in Chile, citizens were pressuring their government to draft a new constitution. While the country vibrated with revolutionary potential, León and Cociña were inspired to reimagine a history with their short Los Huesos (The Bones) (2021).

the ritual begins

Los Huesos claims to be a 1901 film lost to time, only recently dug up in Chile in 2021. This is an obvious fabrication, but the idea is Los Huesos was the first stop-motion film to exist. In the film, a young Indigenous girl is shown enacting a ritual to bring about change while using the bodies of Diego Portales and Jaime Guzmán, major figures in Chile’s authoritarian history.

In this film, León and Cociña reference Ladislas Starevich, a stop-motion pioneer from the silent era. As a filmmaker, Starevich was originally interested in documenting stag beetles, but when they didn’t move the way he wanted, he instead animated dead beetles frame by frame with wires around their legs.

from The Cameraman’s Revenge (1912)

From there, he started making narrative films featuring dead insects as his protagonists. For context, these films are humorous and almost twee, but always with horrifying undertones of death pervading them. Horror has always been inherent in the genre, and León and Cociña exaggerated the horror by reanimating human bodies in Los Huesos.

Even before Starevich, though, the method of stop-motion actually has its roots in the techniques established by Georges Méliès, previosuly featured by ShortHaus last September. The camera stop trick is a technique where the camera is stopped, the scene in front of the camera is subtly changed, then the camera is restarted. This makes it seem as if someone has appeared or disappeared in a flash. Méliès often used this technique and stop-motion to create his famous camera tricks.

from The Vanishing Lady (1896)

To mimic the style of silent-era filmmakers, León and Cociña shot Los Huesos on 16mm film and used heavy vignetting and other artifacts of the age. In contrast with La Casa Lobo, the camera in Los Huesos remains static as elements of the staging move in front of it.

Méliès, with his background as a stage performer, was drawn to using the stage as a feature in his work. Sets were built up with carefully painted flats, as is often the case in theater. The set of Los Huesos is similarly flat, clearly made up of painted backgrounds or even just a dark curtain. Just as Méliès performed his magic in front of a simple black curtain, so too does the little girl of Los Huesos perform her magic ritual for the end of oligarchy in Chile.

from The Four Troublesome Heads (1898)

Los Huesos has its own troublesome heads

Forward Motion

Ari Aster, known for Hereditary (2018) and Midsommar (2019), has been very excited by the work of Cristobal León and Joaquín Cociña, going so far as to produce Los Huesos and their upcoming project. Aster told Variety,

“I’ve said before that they strike me as the successors to Švankmajer and the Quays, their obvious influences tracing all the way back to Starevich, but I have a feeling that they have already started building a unique tradition of their own.”

An important step in building that tradition was made when Aster personally asked them to work on the animation sequence for his most recent film, Beau is Afraid (2023). With this opportunity, León and Cociña were able to spend a year and a half diving into different animation techniques.

behind the scenes of Beau is Afraid

In a panel discussion with Corporación Cultural de La Reina, the duo shared some of the behind-the-scenes details in the making of the scene. In any one shot, they composited hand-painted miniature backdrops, rotoscoped environments and digitally drawn animation alongside their tried-and-true technique of life-size stop-motion.

All of those techniques were carefully layered under and over the live-action performances of Joaquin Phoenix and his anonymous masked costars of the scene. In a Wired article, Cristobal León said,

“We wanted to create something where you could not tell exactly how it’s made. It’s very hard to tell which element is drawn or which element is animated using stop-motion. It was a huge laboratory for working with really talented people and combining techniques. A lucrative and fertile laboratory.”

In contrast to the rest of their work, the duo chose to keep the method of animation more ambiguous on screen. But this helped them master more advanced techniques quickly.

Some of those techniques, such as working with a live actor, have carried on into their most recent work, Los Hiberbóreos (The Hyperboreans) (2024). Though it still isn’t widely available, from the trailer, it’s clear the duo is still interested in the staged effects of Méliès.

from The Infernal Cakewalk (1903)

from Los Hiperbóreos

They’ve also returned to puppetry, which they played with in earlier works such as El Arca (2011). As for their interests in the creative process, it’s still very much a focal point of this work. It’s plainly apparent in the synopsis:

Actress and psychologist Antonia Giesen decides to film a script revealed by a voice within the mind of one of her patients. Seeking collaboration with the filmmaking duo León & Cociña, they craft a crossroads of theatre, science fiction, animation and fabulated biopic, populated by parallel worlds and haunted by the shadow of a Chilean Nazi writer as a demonic figure.

puppets of León and Cociña join live actor Antonia Giesen

If you still want to learn more about this duo, I created a playlist of shorts, trailers and interviews to explore. If you want to make your own stop-motion, don’t hesitate to! Skill will come with experience, as was definitely the case with Cristobal León and Joaquín Cociña.

To learn more about the technique, Adobe has a quick start guide and LinkedIn Learning has an in-depth tutorial. These days, there are plenty of apps to get started with shooting on your phone, or you can check out a camera from Studio 300 and get started today.

Who knows, you might even win the next Short Film Competition just like this year’s past winner, the Godzilla-inspired masterpiece, Abstract Dreams.

It’s plastic