Last month, ShortHaus Cinema featured a director turned producer. In an interesting turn, this month we’re featuring someone who intended to be a producer but turned out to be a spectacular director. Charlotte Wells has made a big splash in recent years with her debut feature Aftersun (2022), and we thought Pride month was the perfect time to feature this up-and-coming queer Scottish director.

from Aftersun, Sophie splashing in the pool, recorded through an old camcorder

Queer stories often focus on the pain of being queer in a world that rejects that existence. Recent years have seen a twist in that trend, where queer characters are allowed to live full lives, and the stories focus more on other aspects of their lives. As a queer creator, Wells’ stories are inherently queer. In a conversation with the LA Times, she said, “My characters are always going to be queer by default… the stories I’m interested in telling are my experience in the world.”

But the characters’ queerness isn’t a defining characteristic, it just kind of is. Far more important is the totality of their lives, which, as a queer non-binary individual myself, is just the kind of narrative I want to see. There will always be room for stories of self-discovery, second adolescence, transition, love, rejection, etc. But for now, let’s look at stories that are tragedies for a multitude of other reasons.

Painting Portraits

While studying painting, my professors always told me the mark of a successful painting is its balance between specificity and ambiguity. Ambiguity keeps it open, lets the viewer in and lets them bring their own experiences to the interpretation. But specificity gives them something to latch onto, something real. This idea can be applied to all the arts, like writing, poetry and even filmmaking.

David Hockey, Portrait of an Artist, 1972, Acrylic on Canvas. Also a queer artist.

Charlotte Wells wields this idea masterfully. She pulls from a deep pool of memory and personal experience to paint heart-wrenchingly beautiful portraits of life’s quiet agonies. All of her work covers a kind of loss, from body and mind to innocence and autonomy. Her method of storytelling relies on subtlety, the ultimate show-don’t-tell. We are never given expositional descriptions of what’s going on. Instead, we are placed in the immediacy of the character’s everyday, their routine, and we can see how those routines are disrupted by tragedy in small moments.

Any Other Tuesday

In Tuesday (2016), Wells’ first film, the routine is clear. It’s Tuesday night, and Allie goes to her dad’s. The deeper significance of that fact is at first concealed from us. The film opens up to mundanity, a teenage Allie hastily mending the torn elbow of an oversized sweater, perhaps not her own, while echoes of family breakfast are heard from below.

Allie walks alone in solitude

Despite her mom’s attempts at connection, Allie rebuffs her and wanders through her day in an anxious haze. She’s late for class, she hasn’t done her homework and she doesn’t even bother to defend herself when the teacher accuses her of partying all weekend. Allie’s friend talks on and on about her own weekend, and Allie only absentmindedly replies, then coldly rejects an offer to hang out, running off with urgency.

When she finally gets to her dad’s place (minute 4:34 of an 11:04 runtime), the pacing slows, but the anxiety is still hanging in the air. Allie attempts to carry on with the routine, grabbing a snack to have while she completes her overdue homework. However, here is where the façade of routine begins to slip, as she cuts an ice cream carton down the middle in a ritual clearly meant for two, but proceeds to eat her half alone and in silence.

slicing a carton of ice cream into sharable portions

The night drags on, and after homework, she needs to find something else to do, still alone. She changes the strings on a guitar she barely knows how to play, plucking discordantly. She wanders aimlessly, looking into drawers, across dressers, through a wallet and receipts left beside a bed not slept in. All these subtle hints—specific rituals broken, daily detritus abandoned—build a heartbreaking narrative. Eventually it clicks: Allie lost her father this weekend, this is not a normal Tuesday and there will never again be a normal Tuesday spent with dad. The last scene shows Allie sitting alone on the couch, eyes wet, while she waits for her mother to pick her up, ending the Tuesday ritual.

Allie alone, in the dark

It’s beautiful and sad. The reality of the situation isn’t entirely clear, and we’re never given all the information. I missed many of the details above on my first viewing, but those specific moments brought such clarity.

Hastily darning

She mends an old sweater, probably her dad’s, to preserve the fabric and prevent further fraying. She knows how to change the strings but hasn’t had enough time to learn the instrument. This apartment is a perfect capsule of life so recently snuffed. All those small tangibilities in this film reveal a greater emotional truth, living for a short time in Allie’s world of fresh grief.

Charlotte Wells is able to paint such a careful portrait because the pain on display in Tuesday is rooted in real grief and memory. This teenage Allie is so close in age to Wells when she lost her own father at sixteen. In conversation with Romy Madley Croft, the two artists spoke at length about their craft and how much of themselves to put into it. Ultimately, Wells concludes succinctly with: “It’s that thing: Universality comes from being as specific as possible to your own experience.” By putting so much on display, Wells connects to large audiences experiencing their own versions of grief, and we’ll see that continue throughout her oeuvre.

Laps in Routine

Wells’ following film, Laps (2016), is also based on memory and depicts an experience far more universal than it ought to be. I won’t go into the film beat by beat because it covers quite a sensitive subject matter: an assault on a busy subway. What I will detail, though, is how Charlotte Wells uses visuals and sound to evoke the exact feeling that kind of traumatic experience produces.

only the eye is in focus in this very tight shot

Nearly the entire film is shot in extreme close-ups; sometimes, just an ear and jawline are in the frame, or a fraction of a phone. She also uses a narrow depth of field to keep only a thin curtain of the space in focus. This framing leaves the moments shrouded in ambiguity, with our understanding of the situation only as clear as the unnamed character’s.

The ambiguity of framing is then made specific through the use of sound, expertly mixed by Kate Bilinski. The shifts in sound are subtle but greatly inform the character’s state of mind. In her typical life, her comfort in marked with muffled tones. The film opens with her normal routine, swimming laps at a city pool, the sound of water drowning out all else (beautifully shot, by the way, by Gregory Oke, who would later lend his cinematography skills to Aftersun). Shortly after, she boards the subway, just like any other day, casually playing a mindless phone game. With headphones in, the world outside her casual comfort is muted, just as it had been muffled underwater mere moments before.

the muted blue-green tones add to the muffled quality of this underwater shot

even the most generic phone game and tangle of headphones are beautifully shot

Then, something shifts, and the mundane is threatened. She tenses her jaw, tears out her headphones and the sound becomes crisp—abrasively so. She is on high alert, but we can’t quite tell why. Until it clicks, and the audio muffles again as if she’s taken back underwater. This time, figuratively, the reality of what’s happening is pulling her under and suffocating. The sound is so evocative of when your mind begins dissociating, where the world becomes so far removed, and your body is no longer your own. The deadened sounds don’t exist as a point of comfort anymore but reveal the complete dulling of her senses.

Laps can be a particularly triggering watch. I wouldn’t recommend it to any survivors of assault, but it is very well done and an important lesson in empathy for those fortunate enough not to share similar experiences. Many have criticized the character’s lack of response: why didn’t she fight back, push away, shout, or do anything? But how someone reacts in that kind of situation is entirely unpredictable, and Wells herself based Laps off her own experience; she shared with Vimeo: “Something not so dissimilar happened to me, and I was disturbed by my capacity for self-doubt by my ability to disassociate in the moment. I had thought of myself as someone who would speak out if something like that happened to me, but I didn’t — far from it. I was interested in exploring that: the gradual escalation, the doubt and fear and panic, and, in this case, an acceptance of sorts that it happened.”

It’s important for works like this to exist, especially when we see such vitriolic reactions online to the question, “If you were alone in the woods, would you rather run into a man or a bear?” Violence like this happens every day, and films covering these subjects, when done right, allow empathy to grow for your fellow humans.

Blue Christmas

Wells’ third short, Blue Christmas (2017), returns to more distant memories, some even before her time. In a 2018 interview with Jim Ross from Take on Cinema, Wells says of the film, “The origin of the story came from a few different places, one of which was my grandparents. I’d been struggling to write another project when I spent some time with my grandfather. One afternoon, he started regaling the family with stories of his time debt collecting which is what he did for the majority of his career. When I was little, I would ride around in the car with him on calls. I found myself then combining aspects of my own life with my grandparents’.”

What we see in Blue Christmas is a lovely blending of Wells’ own tragic memories with the comedy of a debt collector’s daily dealings with people who hate his guts. The film explores a family quietly crumbling under the weight of mental illness. As always Wells deals in ambiguity, so what exactly is wrong with Lily, wife and mother of the story, we’re not made aware of. But we do know how it’s changed the daily lives of this family.

Lily’s introduction

We’re introduced to Lily with Tommy (her son) telling his father (Alec), “Mum says she’s going to set the tree on fire.” Then, the first we actually see of Lily is just her feet clad in mismatched socks, which we know is a common occurrence with Alec’s line: “You’ve mismatched your socks again, love.” Other things are out of place, but Alec carries on casually, subtly letting us know that this is just life now. As Lily mutters about goblins in the tree, he calmly takes the radio antennae from her hand and reinstalls it. When he can’t find his keys, he discovers them inexplicably in a mug on the counter. So many elements of their lives aren’t rigidly defined, but we’re given these crystal-clear glimpses to latch onto.

the missing keys in a dirty mug

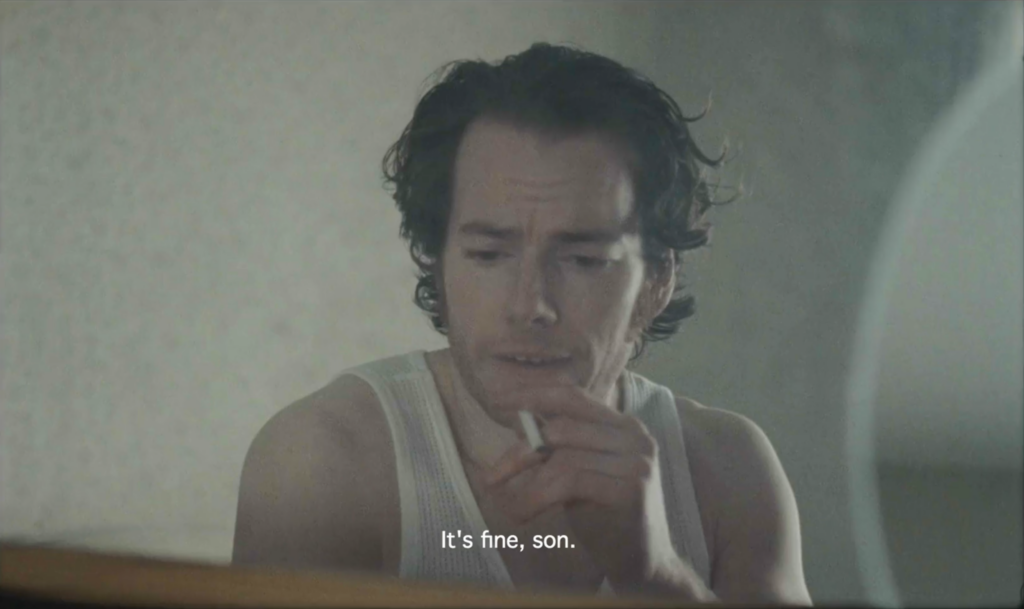

The crux of this story, though, is that it’s Christmas Eve, but Alec is rushing around looking for his keys so he can leave for work on this major holiday. Debt collecting is certainly non-essential, but he would rather carry on with the monotony of work, leaving his fading wife to the charge of their preteen son.

The comedy comes from the juxtaposition of his subsequent house calls. Every one of his stops is rightfully angry that he would come calling on a holiday, one that’s particularly expensive for low-income families. They curse and swear at him, slamming doors in his face. One woman answers the door shirtless and says nothing while he tries casually asking her for the bank’s money.

There’s also lightness in Alec and Lily’s relationship. When he’s anxious to get out the door, and his son is insulting him for working on Christmas, he still stops to start dancing with his wife to “Blue Christmas.” There’s still so much tenderness there, but at the same time, he can’t stand to be around her as her mind deteriorates.

Alec starts his day already drained, immediately lost in the reflection of a dirty mirror

This lovely image returns at the end of the film with more poetic visuals. After spending all day working and avoiding his home life, Alec comes home to find his wife and son with arms locked in struggle, perhaps Tommy trying to stop his mother from setting their home aflame. As Alec calms her, a lit cigarette falls carelessly from her hand, immediately alighting the undecorated Christmas tree. The following scene cuts between fantasy and reality, one where Alec and Lily have one last dance, her socks still mismatched, while the room goes up in flames around them. The other is where Alec grabs her and follows their son out the door. It’s so gorgeous and real, and that motif of dance would again be used in Aftersun.

so much tenderness and warmth

those mismatched socks again

their life burns up around them

Blue Christmas ends up being the most successful of the shorts because it balances that warmth and tenderness with the stark reality. It’s that balance that Wells would carry on to her first feature. She would also carry forward the stories already shown in Tuesday and here. Wells doesn’t like to speak openly about her personal life, especially since so much of it is on display in her work. However, I think it’s safe to say that a lot of her experiences reveal themselves in Tommy, having to live with a parent with mental illness and sometimes act as a caretaker before you’re even old enough to take care of yourself.

A Masterpiece of Memory

Charlotte Wells’ debut feature was extremely well received upon its release, so much so that its list of accolades has its own Wikipedia entry. That response is for a good reason: Aftersun perfectly balances the push and pull of specificity and ambiguity, the mundane and the traumatic, the every day and the tragedy. Through that delicate balance, Aftersun explores the pain of having a parent with mental illness and then later living with the absence of that parent far sooner than most would hope. There’s so much shared love and joy between this father and daughter, Calum and Sophie. But there’s also so much private agony. Agony from the pain Calum is experiencing every day, and agony from a future Sophie trying to understand what he was going through despite the grief she endured living without him.

Sophie and Calum, seen through a nostalgic lens

Memory is again an inspiration, but also acts as a framing device in this story: a thirty-year-old Sophie looks back on a vacation to Turkey with her dad through videos recorded by her eleven-year-old self. Wells described finding the subject of her feature with Gayle Sequeira from Film Companion: “I was flipping through holiday albums and was struck by how young my dad looked on the holidays that I was with him. I was approaching the age he was. And it’s exactly what you said, that when you’re a kid, you confine the adults in your life to the role that they perform for you, and it’s really hard to see them aside from that. As the memory framing of the film came in, it became an opportunity to reflect on that and reevaluate an experience from a new point of view. I was thinking about what that experience was like for him as well.”

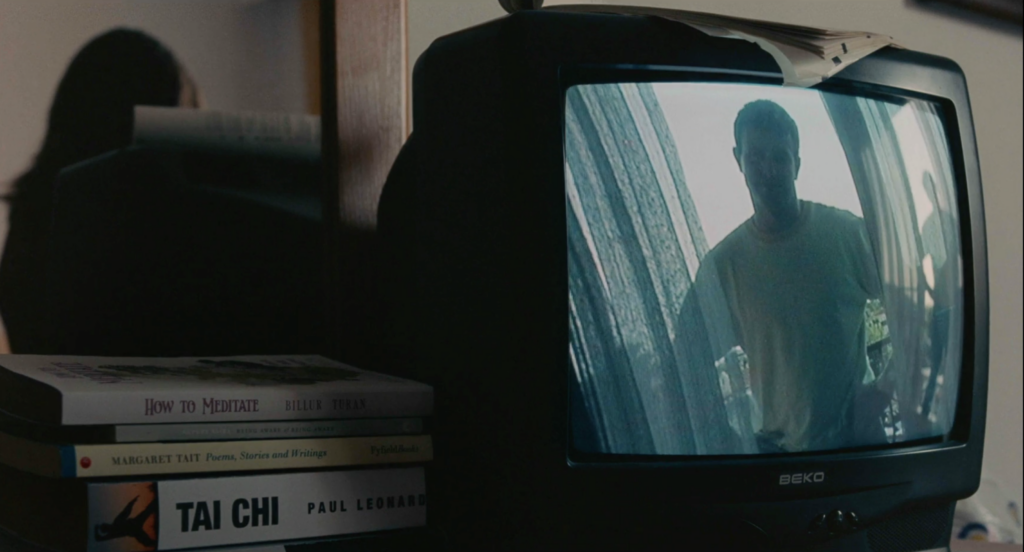

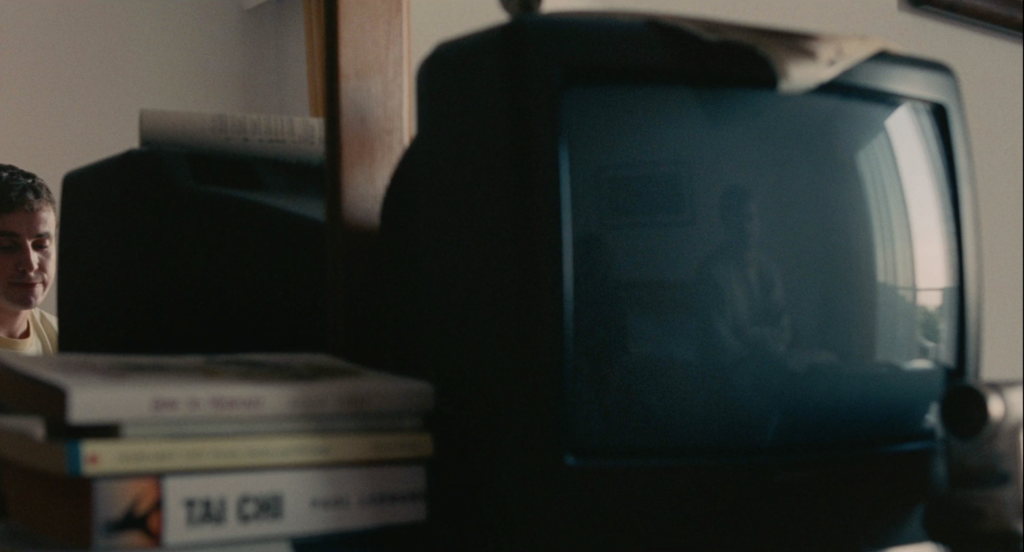

Gregory Oke’s thematically relevant framing comes in clutch to bring this narrative to life. The film opens with one of the recorded videos, but when it pauses, we just barely see the reflection of adult Sophie in the television glass, already structuring the film around her perspective.

Adult Sophie, faintly reflected

Throughout the film, the characters are so often framed in reflection or with literal barriers between them. In some ways this is a practical means of getting both Calum and Sophie in the shot. But it adds to this hazy reflection of what actually happened. Our parents, too, we only know through our interpretation. As a child, they’re your world. At some point, you realize they’re separate beings with their own struggles and emotions, and there are entire walls built up between you and them.

a literal wall separates father and daughter

As I discussed in Alison Maclean: Symbols of the Domestic Space, mirrors are a common symbol of looking internally. But Oke and Wells utilize them to visually represent the layering of reflections and perspectives, an adult Sophie trying to recall the signs of her father’s illness that were captured just out of frame.

One scene in particular has multiple layerings. In Sophie and Calum’s hotel room, a small CRT sits in front of a dresser mirror. The light from the window is reflected across the glass, and when Sophie starts playing a live feed of the camcorder on the TV, Calum is seen in duality as the video records him and the glassy screen reflects his movements simultaneously, one on top of the other. Sophie, meanwhile, is still visible in the shot, reflected in the sliver of mirror squeezed behind the TV. This pivotal scene has Sophie asking her dad questions about his life and his childhood, questions he struggles to answer in his current depressive state. When he finally asks her to turn off the camcorder and sits next to her on the bed, they’re still both seen in the now vacant glass of the TV. This one scene is a three-and-a-half-minute static shot, but the subtle visual shifts in reflection retain your attention the entire duration.

Calum is seen twice over but remains cold and distant, emotionally inaccessible

a softer reflection now, though Calum remains closed off

Wells speaks on that scene, again with Sequeira: “I think reflections play into memory very nicely. I think (cinematographer) Gregory (Oke), too, is drawn towards shooting things through surfaces. The television was in the script, and the reflection didn’t originally play out in the TV—the idea was that they’d be offscreen, but the geography of the room wasn’t set up in a way that would’ve allowed that shot, and so instead Greg found a positioning that allowed for the camera to be turned off and then for you to see them on the bed, which was obviously much better… There’s just so many layers of memory and perspective and refraction and abstraction.”

Preservation

Memories offer a wealth of inspiration, so if you’re a creative, never hesitate to pull from your own experiences. They don’t have to be exact; you can lie, and it’s probably better if you do. A lot of Wells’ work seems so rich and specific that it would have to be a replication of memory, but she actually sought to avoid any direct translations. In that interview with Sequeira, Wells said: “Memories are so amorphous. Even as they’re in your mind, when you try to recreate them, you’re adding a thousand more. And I was very conscious not to overwrite memories that I had by recreating them. I didn’t want to be thinking back to moments that meant something to me and see the film instead of what it is preserved in my mind.”

Utilizing a camcorder throughout the film plays with memory in an interesting way. Memories are so malleable, having video really changes how those memories are preserved. If you rely on the video, at some point your memory of the experience won’t be from your own perspective, but from the perspective of the camera. But an imperfect translation is better than letting the memories slip through your hands, and watching videos back can still trigger the actual memories to flood to the surface once more.

a glitchy rendering of that chess board video

the two photos Wells chose to share of her and her father, who happened to be on vacation in Turkey at the time

Overall, Wells left her memories uncorrupted, aside from a few direct inclusions. For example, video footage of her and her dad playing chess, but only their torsos are visible on the edges of the board, which also happens to be the only video she has of her dad. With Catherine Shoard from the Guardian, Wells said:

“I think that’s kind of perfect in its own horribly sad way. My generation has more than the generation before, and this current generation records more than ever. And yet, sometimes, I still forget to point the camera at things you might wish you had later on. I don’t think that feeling necessarily would ever change, of always reaching for something you don’t quite have. The feeling of chasing somebody lost.”

I, for one, had those memories lost to me, years of family photographs left as cinders in a house fire. There’s a loss of tangible history, just a few odd toys that escaped the fire relatively unscathed, if a little sooty. But I recently found a tape that survived, a poorly labeled VHS with less than twenty minutes of footage, the time stamp in the lower left-hand corner reading “Jul. 30 1996,” my birthday.

lost family footage, found

So now there’s a new memory, seeing two twiggy parents, the same age I am now, staring down at this little bundle of chubby baby that will one day be me.

Join us next Tuesday, June 11, at 7 p.m. in Meeting Room C to discuss this beautiful filmmaker.

Aftersun is available to watch on Kanopy. Charlotte Wells’ shorts are all available to watch on her website. And if you have some memories you want to hold onto a bit longer, come see us in Studio 300 to digitize your tapes, mini DVs, Hi8 and 8mm reels. It’s worth it.