One of the goals of ShortHaus Cinema is to spotlight lesser-known and marginalized directors. So for Black History Month, we chose to feature an integral part of film history, the first Black woman director to get a feature debut, Julie Dash.

Giving Language to the Unheard

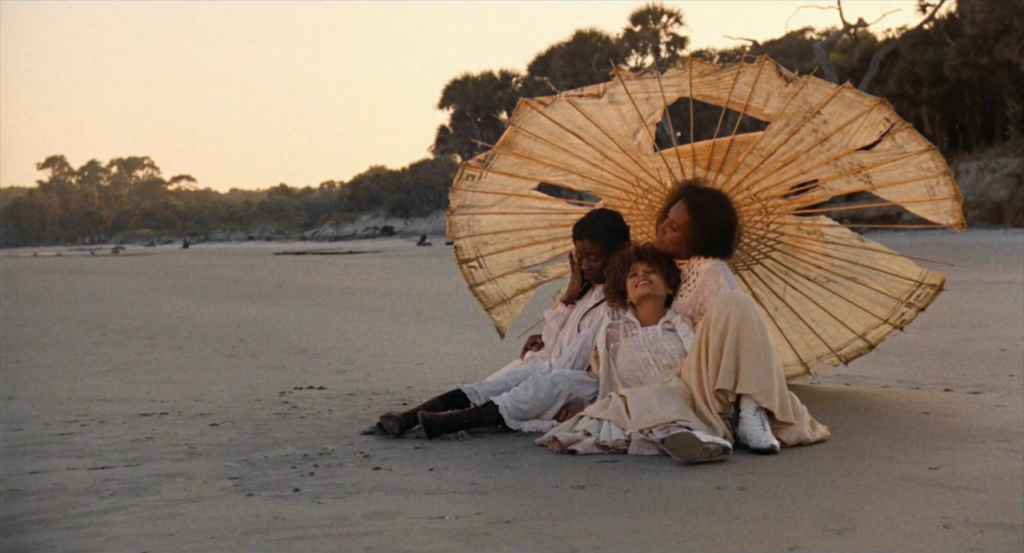

Julie Dash made history with her feature film Daughters of the Dust (1991). Rather than create a story about the urban Black experience, the only experience Hollywood allowed on screen at the time, Dash wanted to explore the vastness of Black history in her work. The project was ten years in the making, as she poured hours, weeks and months into archival research on the Gullah Geechee people of the Sea Islands of South Carolina. The relative isolation of the area lent to a stronger retention of African traditions that spawned a distinct and unique culture.

from Daughters in the Dust

To highlight this specific culture, Dash wanted to create a film with its own visual language and new iconography. The film takes place around the turn of the last century, slavery over, yet its effects rippling out. Instead of the common symbols of slavery like chains and scars, Dash focuses on the quieter violence of indigo processing. Nana Peazant’s hands are stained blue despite decades of freedom, the lingering effects of slavery still very much present in everyday life.

from Daughters of the Dust

Though realistically, the stains would have long faded, they represent a literally toxic past that Nana had to survive, as well as the traditions of growing, harvesting, and dyeing that were brought over from Africa. In defiance, she still wears an indigo-dyed dress while the rest of the women in her family wear more contemporary dresses that are voluminous and white.

At the time of the filming, such agriculturally-based communities as the Gullah were never seen on screen in such finery, but Dash knew special days, such as the family gathering depicted in the film, were marked with more lavish dress and food. In an interview with Vogue, Dash described how, with the help of her production designer Kerry Janes Marshall, she based the costume choices off photographs from the period that placed the Gullah women in Gibson Girl dresses, 10-15 years after the style was popular, most likely hand-me-downs from wealthier white mainland neighbors. To soften the tone of the bright white fabric, the garments were dyed, artificially aged to complement the richer skin tones of her actors.

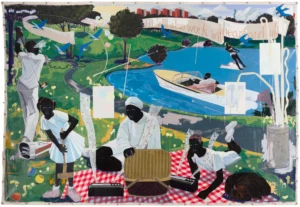

Julie Dash often collaborated with her contemporaries to create her new film language. For Daughters of the Dust, visual artists Arthur Jafa and Kerry James Marshall contributed their expertise as Director of Photography and Production Designer, respectively. In conversation with bell hooks, Dash said:

Kerry James Marshall, Past Times, 1997

“Together, we worked to come up with the tone, the texture, the feel, the sense of place, all of that. We started working on Daughters two years before we went down to shoot it… Kerry brought photographs, drawings, etchings, sketches, whatever he could find, and he’d say, ‘Is this what you mean?’… So we would sit around, I would come up with the theme. Kerry would come to me with ideas that would often broaden the look of the scene, and then A.J. would come up with different ways of shooting it, of lighting it. And that’s how we worked together.”

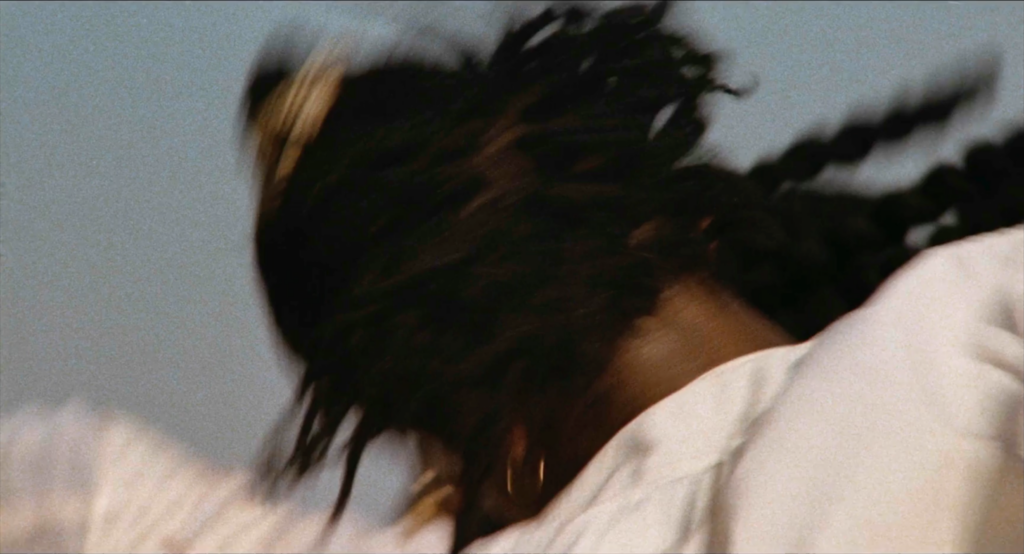

Arthur Jafa added to the film with his evocative cinematography. The secluded nature of the shooting locations made lugging pounds of equipment difficult, so Jafa opted to shoot with natural light.

a thick motion blur can be seen when the FPS drops to a crawl

Following the whims of the sun to give the film a uniquely soft look when compared to Hollywood’s typical lighting. For some scenes where he wanted the film to come to rest, the camera slows below the typical 24 frames per second, giving an unreal, slightly choppy feeling to the movement of actors.

Though rooted in history, many elements of Daughters of the Dust are exaggerated beyond reality, thus offering a greater sense of truth. This leaning toward the more poetic modes of storytelling was formed in the beginning of Dash’s career.

Poetic Beginnings

Dash was no stranger to collaborating and setting historical precedents, as she had already done so with her early short Four Women (1975), one of the first experimental films by a Black director. The film is sparse, just a short seven minutes of a woman, beautifully lit, dancing alone on a stage to the lyrics of Nina Simone’s song “Four Women.” Just as Nina Simone sings as each of the four women, Linda Martina Young costumes herself as each woman and shifts her style of movement to embody each one.

Even Dash changes the editing style slightly, at times pausing the film, halting the fluidity of motion, before cross-dissolving it into the next shot. For a moment between each crossfade, the same woman can be seen twice, in closeup and from far away, adding a sense of multiplicity to her identity, her being. She is Aunt Sarah, Saffronia, Sweet Thing and Peaches all at once. It’s a beautiful, lyrical, visual poem.

from Four Women

Diary of an African Nun (1977) is also a product of collaboration, being based on a short story by Alice Walker (most known for The Color Purple (1982)). Alice Walker is often cited, along with Toni Morrison, as creating new narratives for the Black experience in their writings. Julie Dash was, of course, heavily inspired by their work and adapting Walker’s story gave her the chance to play with more narrative filmmaking.

Even so, the story isn’t quite linear or plotted out, existing more as a cine-poem as the titular nun, Gloria Deum, spends most of the short runtime in her room both agonizing over her barren marriage with Christ and revering him in devotion to her religion. She circles, kneels, prays, raises her hands up, and paces again. Her agony is scored by the constant beating of drums and chanting as the villagers express their own pagan religious fervor, a sharp contrast to the conservative and regimented expressions of belief that Gloria is allowed. And with no physical husband to dance with, she can only gaze at and praise a small icon of her belief, a crucifix we are given every inch of in extreme closeup.

Gloria made small within the frame

a crucifix dominates the frame

In an interview with Barbara McCullough, Dash describes her desire to adapt Walker’s story: “This particular story about a Black nun in Africa shrouded in whiteness and working as a tool of the missionaries but leading a very austere, barren, tormented life, was a very unique story and it was… it had a very special quality about it… I wanted to visualize her conflict and the struggle she was going through.” And visualize she did, with the constant cutting between Gloria, her artificial husband, and the window that separates her from the outside world, Dash builds up a rhythm of anxiety that truly captures the liminal space Gloria has trapped herself in, between whiteness and her people.

As Gloria prays, she is distracted by the revelry outside

Certain elements of Diary of an African Nun feel prototypical for Dash’s work. The way Gloria’s all-white habit drapes across her body feels like a precursor to the billowy dresses of the Gullah women seen in Daughters of the Dust. There’s also a distinctly non-linear element shown in a scene in which the nun is describing her youth. Growing up, she attended the mission school where she now resides, admiring the nuns who taught her. As she narrates this part of her diary, we see a teenage girl and her friends talking to two nuns.

The unnamed girl run down the hill

the Unborn Child runs across the beach

Gloria steps into frame

With context, we would think this girl to be our protagonist from years before, yet when the girl breaks away and joins her family, Gloria steps in front of the camera and walks through the foreground, confusing the interpretation. Is this a separate girl, simply one of the new students of the mission school, or has the act of writing in her diary allowed Gloria a moment to step back into her past as her future self? This strange blending of past and future is used as a core piece of the narrative in Daughters of the Dust, where the Unborn Child occasionally runs across the screen and narrates the story, despite still growing in her mother’s womb over the course of the film’s events.

The Illusion of Filmmaking

Dash continued honing her cinematic language in Illusions (1983), in which she focused on the visual language of framing to enhance her illusory narrative. In the short film, a Black woman passing as white is able to rise through the ranks in a Hollywood production company in 1942. In her position, Mignon Dupree thinks she’ll be able to make subtle changes in terms of the representation of marginalized people on the silver screen. However, she can’t even convince her boss to produce a film about the Navajo Code Talkers, who sent coded messages during WWII using their language—an inherently more interesting story than the blank white heroes in the propaganda films they’d been making. It’s not until she works with a young Black singer that her passion is reignited.

When Mignon walks into the office at the start of the film, the framing of the camera hides her identity from the audience, showing us only from her elbows down as she receives a telegram and speaks with seated secretaries. When her head is finally revealed, her face is still obscured by a black chenille veil. Her identity is obscured from us just as it is obscured from her colleagues.

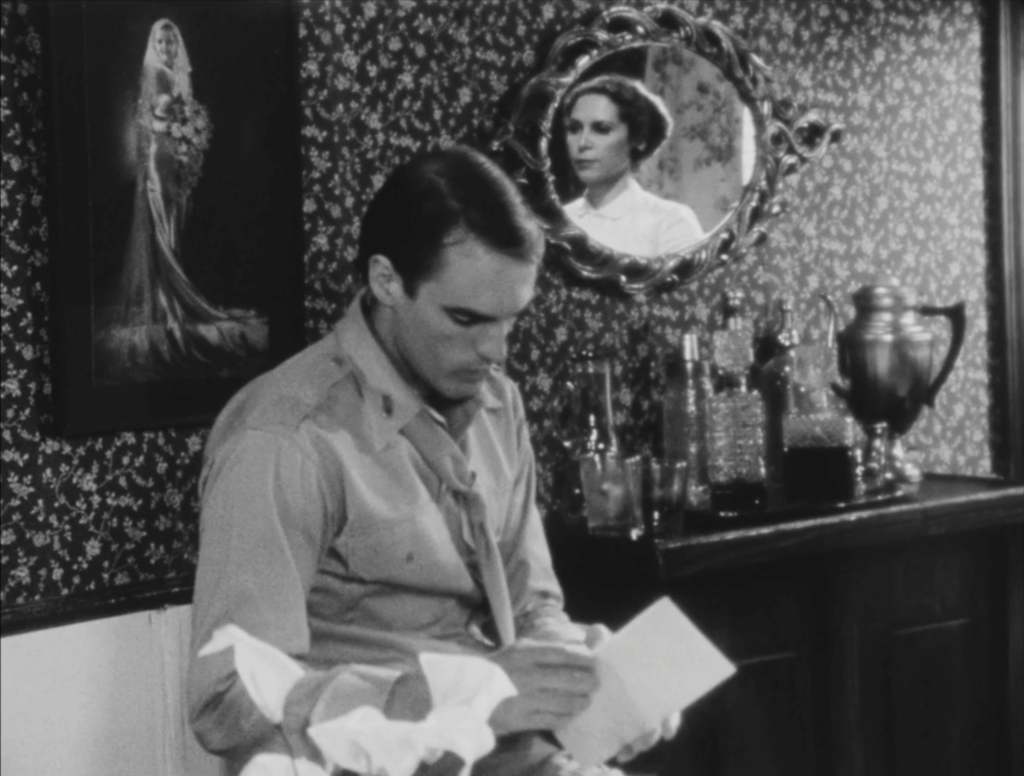

from Illusions

from Illusions

Mignon’s first task on this day is salvaging a film where the audio track has come out of sync. From the audio engineering booth, she watches a silver screen playing the footage of a young blonde actress mouthing the words to a song she cannot sing. The audio engineers suggest having a singer rerecord the song while matching the actress’s mouth, an early form of audio dubbing.

When they turn the studio lights on, it is revealed that the young Black singer, Ester Jeeter, has been sitting in the dark this entire time, quietly watching the picture play as white and white-passing producers and sound engineers work from the comfort of their glass box. When she begins singing, though, she is properly lit, set apart from the bleak black background. The white actress, who was so clearly seen moments before, fades into white highlights when sharing the screen with Ester.

Ester on the soundstage

This act of lighting a Black actress is itself a revolutionary one, as so many directors still set the exposure for their white actors without making any additional lighting considerations for their Black counterparts. In conversation with Jenn Nkiru, Dash spoke about getting the tonality right:

“When I made Illusions, I wanted the black to be velvety, and we could only do that with black-and-white reversal film to get that dark in the shadow areas. I wanted it to look like those old Hollywood movies. Now, with digital filmmaking, it’s all different. You could dial it up to be whatever you want it to be and play with the beauty within the shadow. But then I see commercials today and some films that are shot digitally, and they let Black people go off into the darkness, and you can’t see any facial features.”

from Illusions

She goes on to explain, “Wait a minute? That was solved 30 years ago. There’s no excuse for this! Just because there’s a two-stop difference between light skin and dark skin, they try to separate people. In the old days, they would take the person who’s brown skin and pull ’em out of the scene.” Even today, Dash finds it hard to work with people who refuse to light each and every actor properly.

Outside of lighting, what this scene truly reveals is the illusion of film, the cultural appropriation and the audio blackface used to make the tone-deaf actress appear talented. Her mouth is seen moving, but a Black singer’s voice fills the silence. The illusion takes on another layer, as Julie Dash chose to dub even Ester’s voice with the singing of Ella Fitzgerald. Filmmaking is a flimsy affair when looking at each piece individually, but when it comes together, great truths (and untruths) can be spoken.

Visibility on the Silver Screen

While Mignon speaks with Ester, the Lieutenant overseeing the propaganda films casually invades Mignon’s space and looks at papers on her desk. He discovers a letter and photo from her husband and, from this, discovers that Mignon is actually Black.

When he calls her out, he accuses her of lying to get ahead and even says she’s a different person than she was that morning. But Mignon doesn’t bat an eye, defending her position and making it clear she will not step aside. She will continue fighting to get the stories of marginalized people, telling him blatantly: “Your scissors and your paste method have eliminated my history, my participation in this country… And the influence of the screen cannot be overestimated.”

Mignon speaks through the illusion

With ShortHaus, we want to acknowledge the power that representation holds. Julie Dash will mark the 12th and final director of our first year of ShortHaus Cinema, where we’ve featured Les Blank, Cheryl Dunye, Buster Keaton, Ryan Coogler, Maya Deren, Akira Kurosawa, Georges Méliès, Alison Maclean, Ridley Scott, Jim Henson, Lutz Dammbeck, and Julie Dash. It’s not a perfect list, but a third of the directors are Black, a quarter are women, and another quarter are international directors (more if you count the British one). With these directors, we’ve explored a multitude of stories, all of which are still available on Kanopy to watch anytime.

We want to continue to focus on the underrepresented and allow them to tell their stories. Our next selection of directors Is Alice Guy-Blache, Farah Nabulsi, and George Lucas. Lucas is a bit of fun, but for Women’s History Month, we wanted to focus on a forgotten trailblazer. Guy-Blache. Also, not many may know that as of 2021, April is Arab-American Heritage Month. With the ongoing conflict in Palestine, we wanted to focus on the artistic efforts of Palestinian creators. Farah Nabulsi is one of the few directors of Palestinian heritage with work available on Kanopy, and we’re excited to dive into her work this April.

On a lighter note, we also want to encourage the growth of the burgeoning filmmakers in our midst, and are happy to announce the first Short Film Competition presented by ShortHaus Cinema. The competition will require participants to complete a short film in the span of one week, including all scripting, shooting and editing. It will be a challenge, but we’re excited to see what you create. The first meeting will be on Tuesday, March 5, at 6 p.m. before the next regular ShortHaus meeting. There, we will discuss the rules and hand out prompts to get you started. Then, we’ll have everyone return on Tuesday, March 12, at 7 p.m. to watch everyone’s films and vote on the winners.

ShortHaus Cinema will be meeting this upcoming Tuesday, February 6, at 7 p.m. to discuss the films of Julie Dash. Each film mentioned here is available to watch for free on Kanopy, and a DVD copy of Daughters of the Dust is also available for checkout.

Research for Dash’s work on Daughters and Illusions came from Daughters of the Dust: The Making of an African American Woman’s Film (1992) and Screenplays of the African American Experience (1991), both of which are available through interlibrary loan.